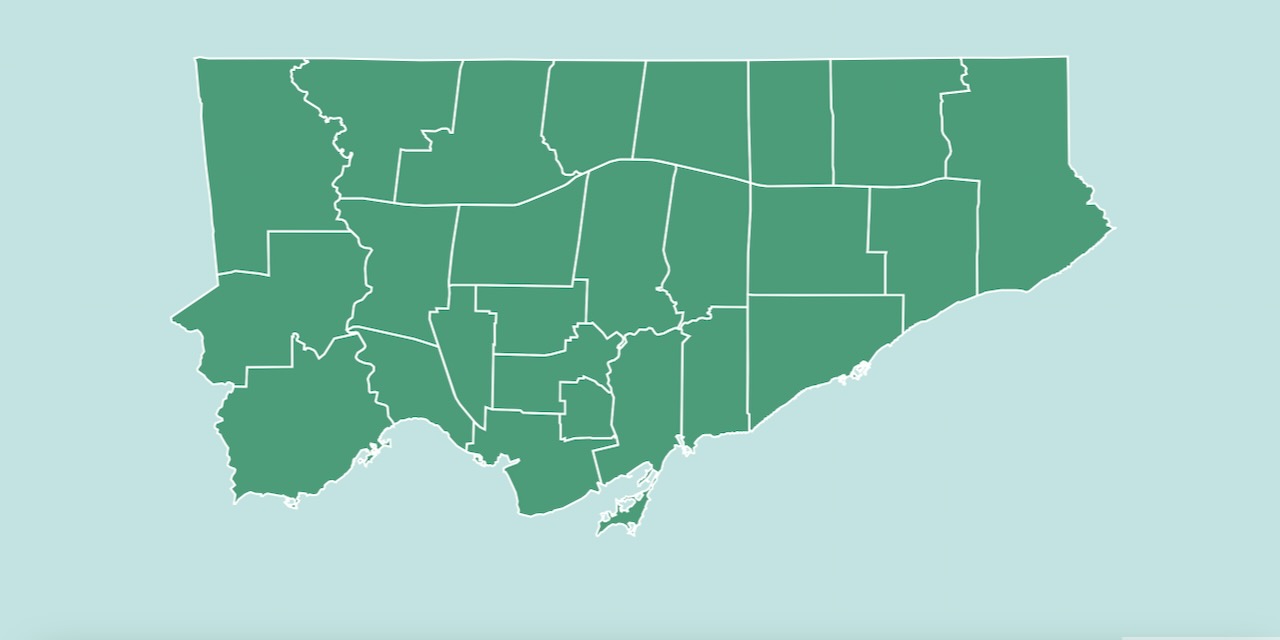

It’s a cliche to say that Toronto is a city of neighbourhoods, but at no time is that more apparent than during a mayoral election. The amalgamated Toronto is a collection of vastly different communities with different demographics, priorities, and needs. And during an election, those differences often find their way onto the ballot.

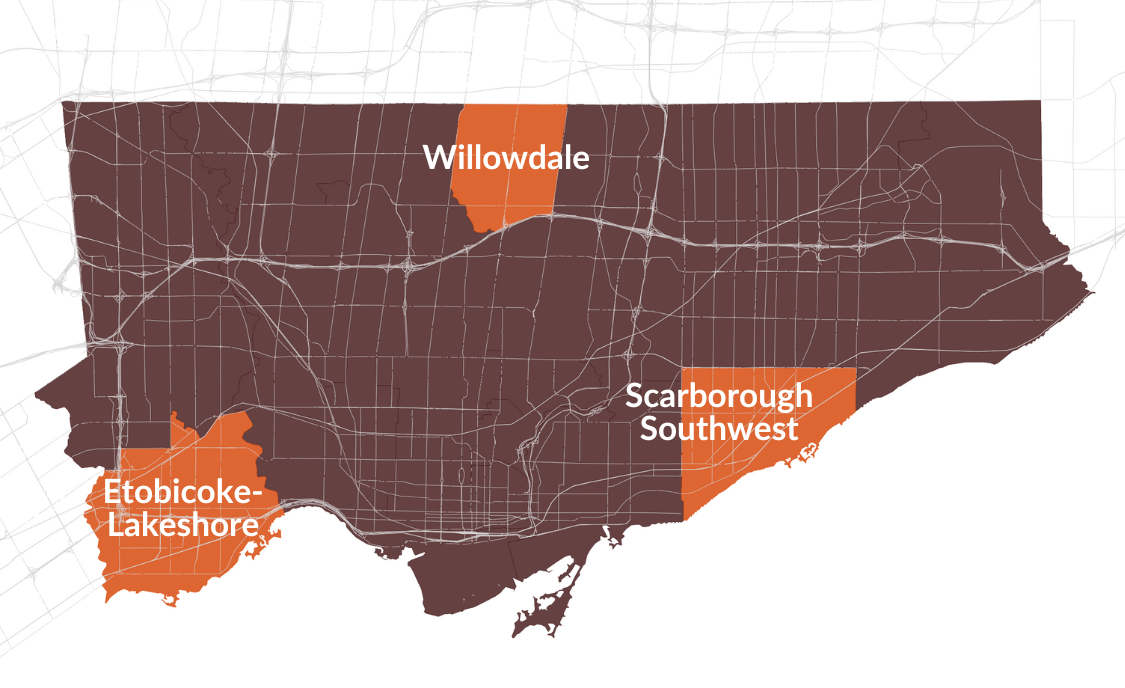

Citywide polling data can’t tell the story of an election. For that, you have to look closer. And while much of the media coverage and many of the campaign events are clustered within the old city of Toronto, elections are often decided far from the core—in places like Etobicoke-Lakeshore, Willowdale, and Scarborough Southwest.

In the recent 2022 election, John Tory won in all 25 wards, but that vote was an anomaly. In 2014, the last election without an incumbent, Doug Ford dominated on the outskirts of the city, in north Etobicoke and Scarborough, while Olivia Chow collected support downtown, and eventual winner John Tory racked up votes in the wide swathe of the city running from north to south along the Yonge subway line.

It’s hard to slot swing wards like Etobicoke-Lakeshore and Scarborough Southwest into neat political categories. The former voted for a young, progressive underdog councillor (Amber Morley) while also re-electing John Tory with 67 percent of the vote in 2022; the latter swung from voting for David Miller in 2003 to Ford and Tory in 2010 and 2014. Willowdale, in contrast, has been a Tory stronghold as far back as his 2003 run. This year, there are no incumbents and a host of polarizing frontrunners.

Whoever wins, in these wards and in the race overall, will need to be mayor for the entire city, representing communities from Etobicoke to Scarborough that sometimes have contrasting ideas about how this city should be governed. Here’s a hyper-local look at what’s on residents’ minds in these three suburban wards.

Elections in the ward are notoriously hard to predict. Currently, you can find representatives from all across the political spectrum: a Conservative MPP, a Liberal MP and a young, progressive city councillor.

With so many people living in the area under so many different circumstances, it’s a microcosm of many of the major issues that will be contested in the upcoming mayoral by-election—especially housing, affordability and transit.

“The community is growing very rapidly and our demographics are shifting along with that growth,” says Amber Morley, who narrowly defeated the ward’s nearly two-decade incumbent, John Tory-endorsed councillor Mark Grimes in the 2022 election.

“There are lots of young professionals who’ve chosen Etobicoke-Lakeshore as home and are working to build a life here. But we also have quite a significant population of seniors and folks who are aging along with their homes or existing rental units, and we have to make sure that we are growing in a way that’s appropriate and supportive of both.”

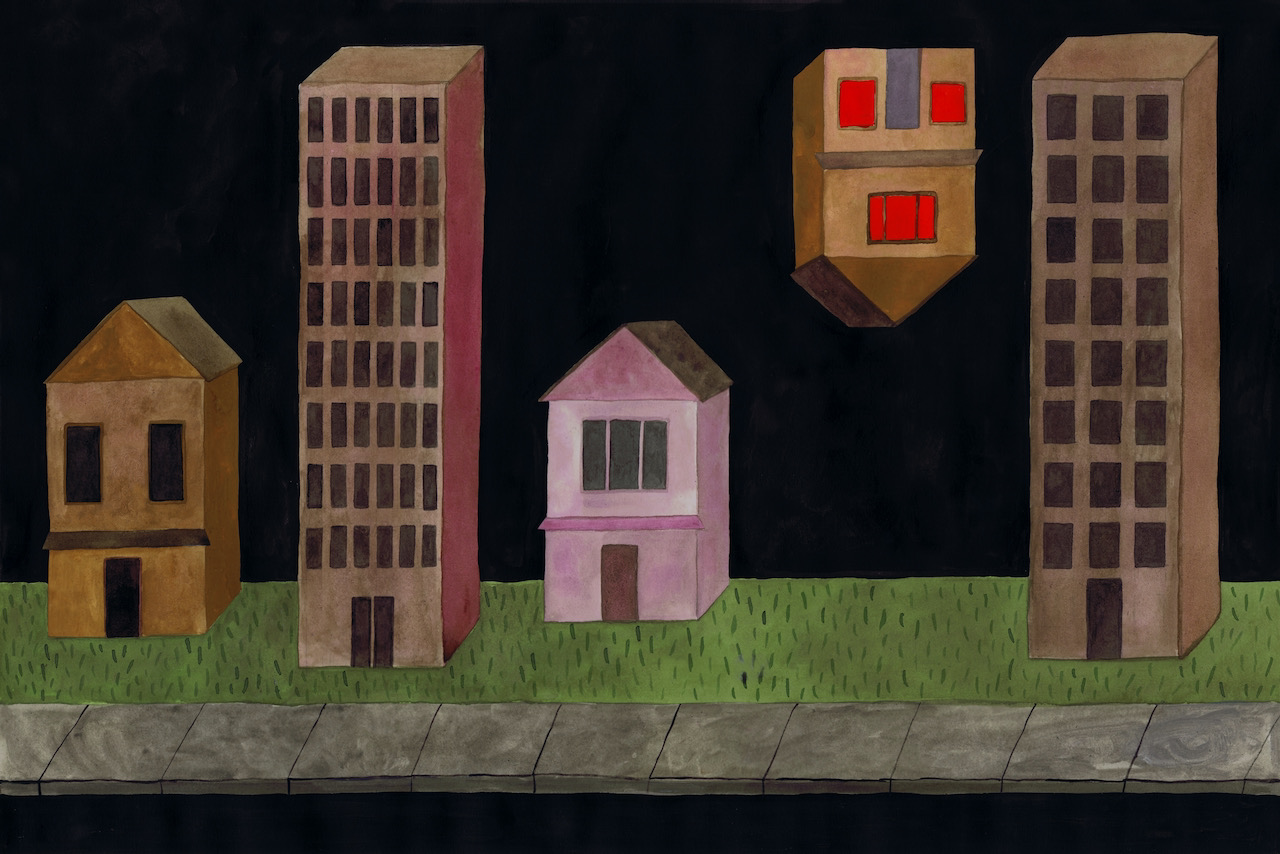

Etobicoke-Lakeshore is one of the fastest-growing wards in the city, with a nearly 10 percent population growth to more than 141,000 between 2016 and 2021. So it’s no surprise to see the area densifying, with new developments sprouting up around Kipling Station and at Humber Bay Shores, where downtown-style condo clusters now scrape the sky on the waterfront. But the rapid development has driven up once-affordable rents elsewhere in the ward—in some cases, it’s also displacing residents who’ve lived in the area for decades.

That cross-section was evident on June 16, when young families, seniors, renters and homeowners all queued up for hot dogs at an “anti-demoviction party” on the lawn between the midrise apartments of 220, 230 and 240 Lake Promenade, part of an aging eight-acre Long Branch complex slated for demolition and redevelopment.

“It would be Canada’s biggest demoviction ever,” says organizer Patti Pokorchak, a resident of 230 Lake Promenade. “It’s 548 units, which is over 1,000 people conservatively… The majority of people have been here at least a decade. There’s a couple in their 80s who don’t have internet, they don’t have cars, they are fragile [and use] walkers. They’ve been here 53 years. Where are they going to go?”

Pokorchak describes the plan as a “phased-in demoviction” in which buildings are torn down one by one, and their residents moved to other buildings. But this disrupts the social fabric of residents who’ve lived there for years, and there are worries that Doug Ford’s recently passed provincial Helping Homebuyers, Protecting Tenants Act, Bill 97, will hinder their once-protected rights to return.

Affordability and housing are a major part of every serious candidate’s platform—especially Olivia Chow, Josh Matlow, Ana Bailão, and Mitzie Hunter. Pokorchak has been courting Chow’s support in the fight to stop the demolitions (it caught her attention: Chow referenced the demovictions at a candidate’s debate the night of the party). The current leading candidate, Pokorchak says, “has a heart for tenants” and has made protections for renters one of her main areas of focus.

The local councillor, Morley, jibes with those ideals as well. She describes herself as “a young racialized girl from the city who grew up low-income in local co-ops,” and is a part of the community she serves. It can be risky for a new councillor to publicly endorse a candidate because they will have to work with the mayor regardless of who is elected, but Morley (who was once endorsed by Matlow for her own city council campaign) has chosen to throw her support behind Chow.

“In my estimation, a Mayor Chow would have the character and reputation [for the job] and has shown through her life’s work her commitment to equity, inclusion and good governance,” Morley says.

See All 102 Mayoral Candidates

Candidate Tracker has fact-checked biographies and platform summaries for every name on the ballot. Also available in print at your local library.

But there are also multi-million dollar homeowners in the ward, some of whom are vocally concerned with Chow’s promise to raise property taxes to fund social services. It’s one way in which affordability and housing—no matter which side of the political spectrum residents are on—could determine which box they check at the voting booth.

For Jasmin Dooh, community relations manager at South Etobicoke’s LAMP Community Health Centre, affordability is also ultimately a health issue. “Many people are struggling so much with affordability that they can’t meet their basic needs like food because it’s all going to rent,” she says.

Last month, LAMP invited the ward’s municipal, provincial, and federal representatives to an affordable housing town hall in which they sourced a list of all the government-owned land in the area. The next step is to “unlock” the land, source funding, and develop “deeply affordable” housing, like rent-geared-to-income units.

She’s proud of how the organizations engaged all three representatives, from the left, right and middle of the spectrum, towards the same end. They’ve started a working group towards an Etobicoke Lakeshore Land Trust, and they’re looking at ways to protect existing affordable housing stock.

No matter who the mayor is, Dooh hopes they can fast-track this initiative. She also hopes a new mayor would support rent controls, work with community groups and other levels of government, and support portable housing subsidies for those who are displaced and cannot afford market rate. “They have to demonstrate results quickly, because it is an urgent need,” she says.

That’s an issue that will determine the election, but will also transcend it.

“It’s got to be a multi-faceted solution,” she says. “You can’t just do one thing. You have to do everything you can.”

It’s a mostly middle-class community, with a majority of people making around $80,000 a year. (Willowdale East, however, is a wealthier enclave, with houses averaging over $2 million a sale.) While population growth has slowed since 2016, it is poised to increase again. Nearly two dozen projects are slated to be built in the next two years.

But that growth has also created tension in Willowdale that has driven its electoral battles for the last year.

“I think we’re at a place now where there’s a consensus of: we need to build all kinds of different types of housing as quickly as we can to solve some of these affordability challenges,” says Markus O’Brien Fehr, who ran for city councillor in the election last fall, and is now volunteering for Ana Bailao’s campaign for mayor. “Locally there has been some very specific pushback to some of the lower-income housing initiatives in particular.”

Last fall, a new modular supportive housing site in Willowdale became a flashpoint during the election. A total of 59 new units were slated for construction at 175 Cummer Road—housing that would go to those with the greatest need, at a time when the city has been grappling with a growing number of people living on Toronto’s streets. But local residents complained that it was too big, too close to a local senior’s home. While Fehr supported the construction, his rival Lily Cheng repeatedly argued that 59 residents was too many. “If you put 59 people who are complex and hurting, it will negatively affect the people who are trying to get better in that housing, as well as the surrounding community,” she said in a candidates’ meeting during her campaign.

Cheng won the ward in 2022, with just eight percent more of the vote than Fehr. She attempted to defer the site from going forward at a June 15 council meeting, but her motions failed, with the relocation proposal losing 2-18.

Fehr points out this one niche issue may not carry as much weight the further you get from this small community—but overall, housing remains a pressure point in North York.

“Affordability of life in general is a big issue, I would say, for my clients,” says Sara Ageorlo, a staff lawyer at Willowdale Community Legal Services. She works primarily on social benefits cases. Her single clients on Ontario Works only get $733 a month—nowhere near the amount needed to cover the average rent of a one-bedroom in Willowdale or anywhere else in the city.

Just past the eastern boundary of Willowdale, redevelopment at Bayview Village promises sleek new highrises and an “urban town square.” Disagreements about the development’s impact on local infrastructure and transit have been taking place for the last three years. “If you drive east from Yonge and Sheppard, condos are just popping up,” says Florencio Almeron, a member of Justice Makers, a working group within Willowdale Community Legal Services, which advocates for affordable housing units in the area and in neighbouring Don Valley North. Ideally, the housing projects in the area would also consider what the ward needs as its population grows—parks, libraries, better transit, safer and less congested roads.

“I do think that in Willowdale, for low-income folks…there could be an increase in things like grocery stores,” says Ageorlo. Ten minutes from Willowdale, a new 36,000 square foot T&T Supermarket opened in Fairview Mall this year, and has proven to be wildly popular. But it speaks to the demand that is imminent once all of these new condo construction projects are complete: thousands of people will be living in the neighbourhood, all of them needing places to get groceries, borrow books and have recreation options.

Where does that leave the candidates? Chow still maintains a strong lead in citywide polls, but her left-wing bonafides may not play well in a community Fehr describes as deeply centrist. In 2014, when Tory and Chow faced off, Tory had twice as many votes. “I think if you look at results of past provincial and federal elections as well, it can flip back and forth between Liberal and Conservative, but the NDP support typically is very, very small,” he says.

But Almeron says the candidates prioritizing affordable housing are most likely to sway Willowdale voters. It speaks to a problem that is felt in Willowdale and beyond: Toronto, for many, is far too expensive to live in.

These regional distinctions have made Scarborough Southwest a historically competitive ward. In 2014, when John Tory was first elected to office, he won the ward by a narrow margin, of less than 5 percent over then-competitor Olivia Chow. In November’s municipal election, Tory ally and 12-year incumbent Gary Crawford scrimped to a similarly tight victory over second-place candidate Parthi Kandavel, who had served as TDSB trustee.

According to the 2016 census, two-thirds of households in Oakridge define themselves as renters, and over 40 percent describe their housing as unaffordable. The likelihood of a resident living in a prohibitively small home, or one in need of serious repairs, is almost double that of the citywide average. Residents are also twice as likely to be unemployed, with households scraping by on just over half the median income of the average Torontonian. Three-quarters of the area’s residents are visible minorities.

Kevin Rupasinghe, a community advocate who previously worked with Cycle Toronto and the Ranked Ballot Initiative of Toronto, and who placed third in the race for city councillor in Scarborough Southwest last November, door-knocked in some of these high-rises during his campaign. The homes, he says, are routinely ignored by those running for political office due to their high concentration of non-voting residents like new immigrants and refugees.

“It was incredible how many people said I was the first candidate they’ve seen since they lived here,” he says. “No one ever knocked on their door and talked to them.”

Martin Malaison and John Kennedy, a couple who have been residents of Oakridge since 2007 and 2018 respectively, say their community has never been more deprived of social services.

“There’s a gap in what needs to be offered and what’s being offered right now,” says Malaison. “There are literally people starving in our very neighbourhoods because they’re not able to pay rent and buy food.”

Suman Roy, the founder and executive director of Feed Scarborough, which operates five food banks in the ward, says that demand for their services has more than doubled over the last year. Meanwhile, the affordability crisis has made procuring nutritious meals more difficult than ever.

“We got slammed both ways,” he says. “On one hand, the cost of food has gone up, so we’re buying a lot less than what we were buying a year ago. On the other, individual donations have gone down by less than half. It’s a balancing act, and it’s hurting us. We’re not the only food bank hurting in the city.”

South of Oakridge, in Birchcliffe-Cliffside, the median household income is over $70,000, nearly double that of the neighbourhood just 10 minutes north, and the proportion of visible minorities and renters plummets to well below the city average. Residents of the neighbourhood enjoy vast public parks and beachside amenities around the Scarborough Bluffs, including the Bluffer’s Park Yacht Club.

Going into the by-election, transit, affordability, and road safety are major wedge issues in Scarborough Southwest. In neighbourhoods like Oakridge and Kennedy Park, half the working population reports taking public transit to their jobs. Like much of Scarborough, the community has suffered disproportionately from recent cuts to TTC service, co-signed by Crawford, Tory’s budget chief.

Malaison, who alternates between driving, biking, and taking public transit to his job at Gears Bike Shop downtown, says “getting across the city is impossible.”

When it isn’t delays in TTC service, it’s congestion and a lack of road maintenance that make it difficult for him to commute through the city.

“We spent about $10,000 getting the car fixed last year,” says Kennedy, after the couple repeatedly broke the springs in their Volkswagon going over potholes.

Then, there are the more dire consequences of a lack of road safety. The city’s road safety tracker shows that 15 people were seriously injured and three killed in the ward last year.

“Literally every neighbourhood we went to, road safety was a concern,” says Rupasinghe. “I met multiple people who shared with me that they had been in a collision. We have people who go out for the day and don’t come home. It’s totally unnecessary. We know how to build streets that are safe for everybody, but for whatever reason we are stalling.”

Whoever takes office, Rupasinghe says it is imperative they have a vision for the future of Scarborough Southwest.

Along the northern boundary of the ward, the opening of the Eglinton Crosstown is set to transform the Golden Mile with 32,000 residential units and a million square feet of retail space set to be developed along the line. Similar developments with mixed-use buildings up to 42 storeys high are coming to Scarborough Junction and Birchmount Park. Condominiums have already begun to crop up along Kingston Road as part of a long-term revitalization plan by the city, despite complaints by neighbouring homeowners.

Like Etobicoke-Lakeshore, Willowdale, and much of the rest of the city, this boom in intensification is set to radically transform the ward in the coming years. Toronto’s new mayor will have to respond to the existing community’s concerns about congestion, noise, and gentrification, while ensuring that the slate of public amenities such density will bring are equitably distributed and made available to the area’s most underserved residents.

“We can’t be thinking about Scarborough 10, 20, 30 years in the past. We have to start thinking about its future and start preparing for it,” Rupasinghe says. “There is an enormous amount of change coming.”