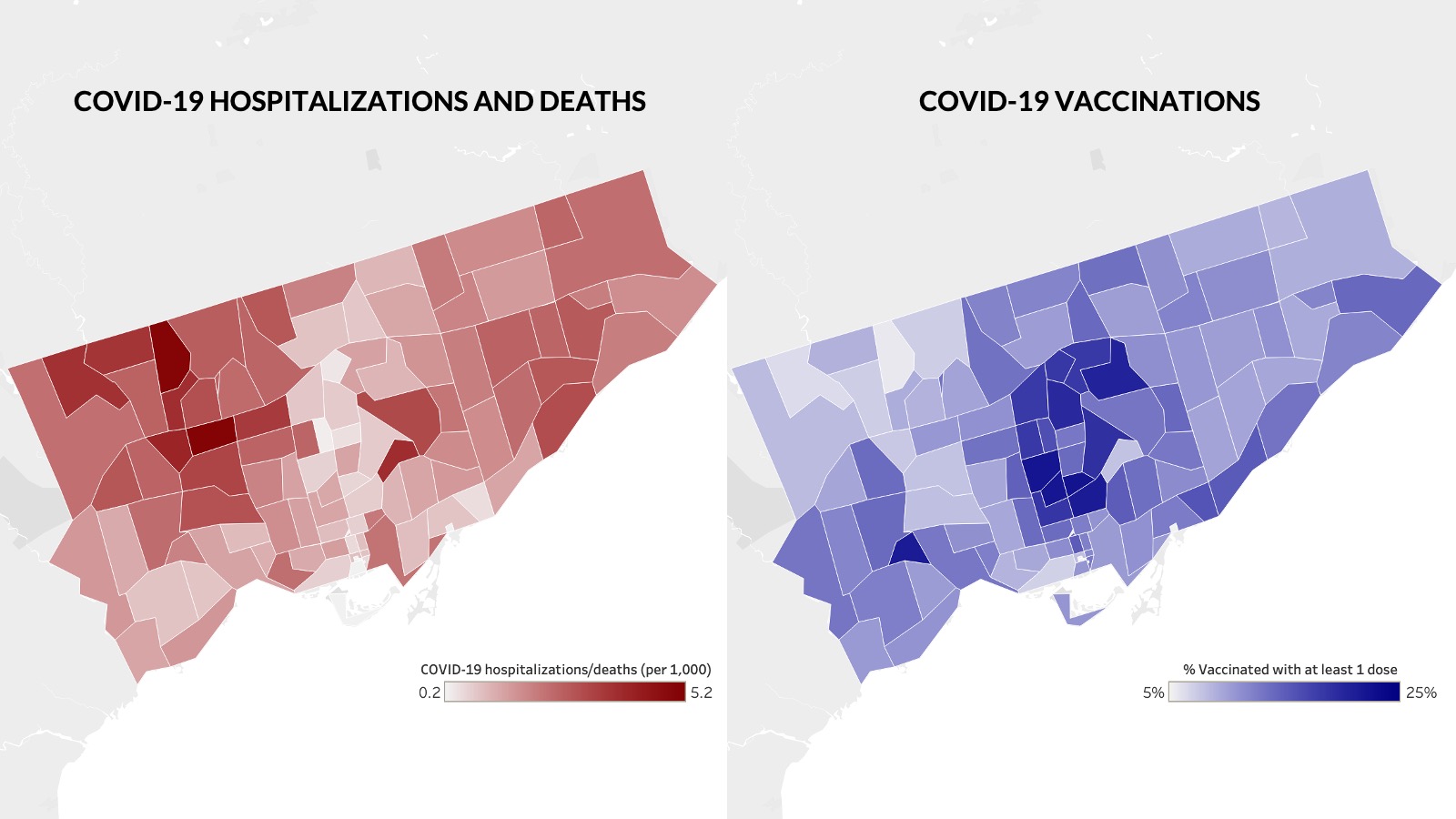

The Toronto neighbourhoods with the highest COVID rates are the least vaccinated areas in the city, according to new analysis from the Toronto-based independent research group ICES.

The report, published this afternoon, is the first in-depth look at who is being vaccinated in Toronto at a neighbourhood level. It reveals a stark mismatch between who needs the vaccine and who is receiving it.

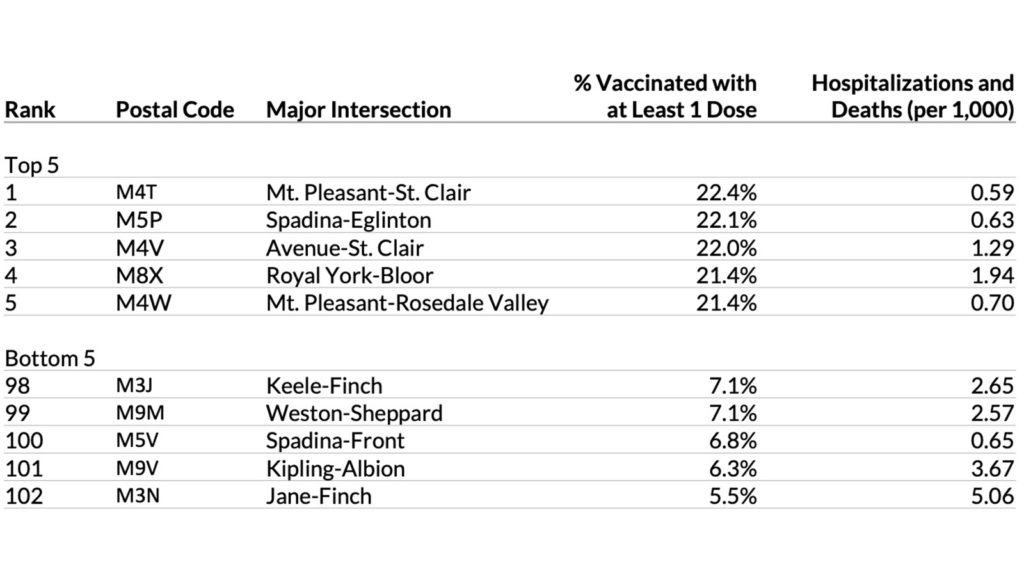

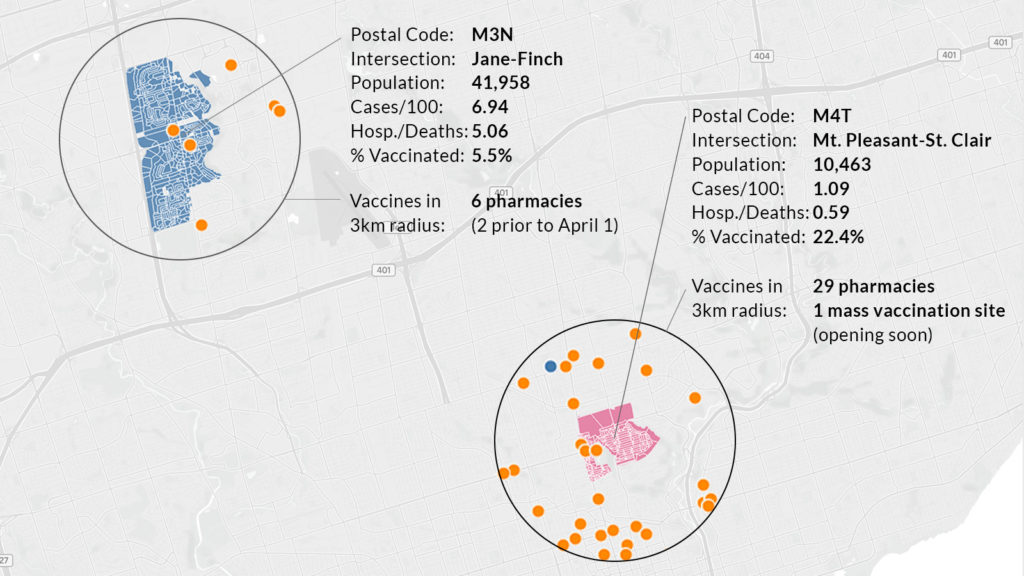

The data, which spans until March 29, shows that postal codes beginning with M3N, the area around Jane and Finch, have the worst COVID rates in the city and the second worst rates of hospitalizations and deaths. Yet just 5.5 percent of residents have received one or more vaccinations, the lowest rate in the city.

In contrast, M4T, the Moore Park neighbourhood at Mt. Pleasant and St. Clair, has among the lowest rates of hospitalizations and deaths. There, 22.4 percent of the population has been vaccinated, the city’s highest rate.

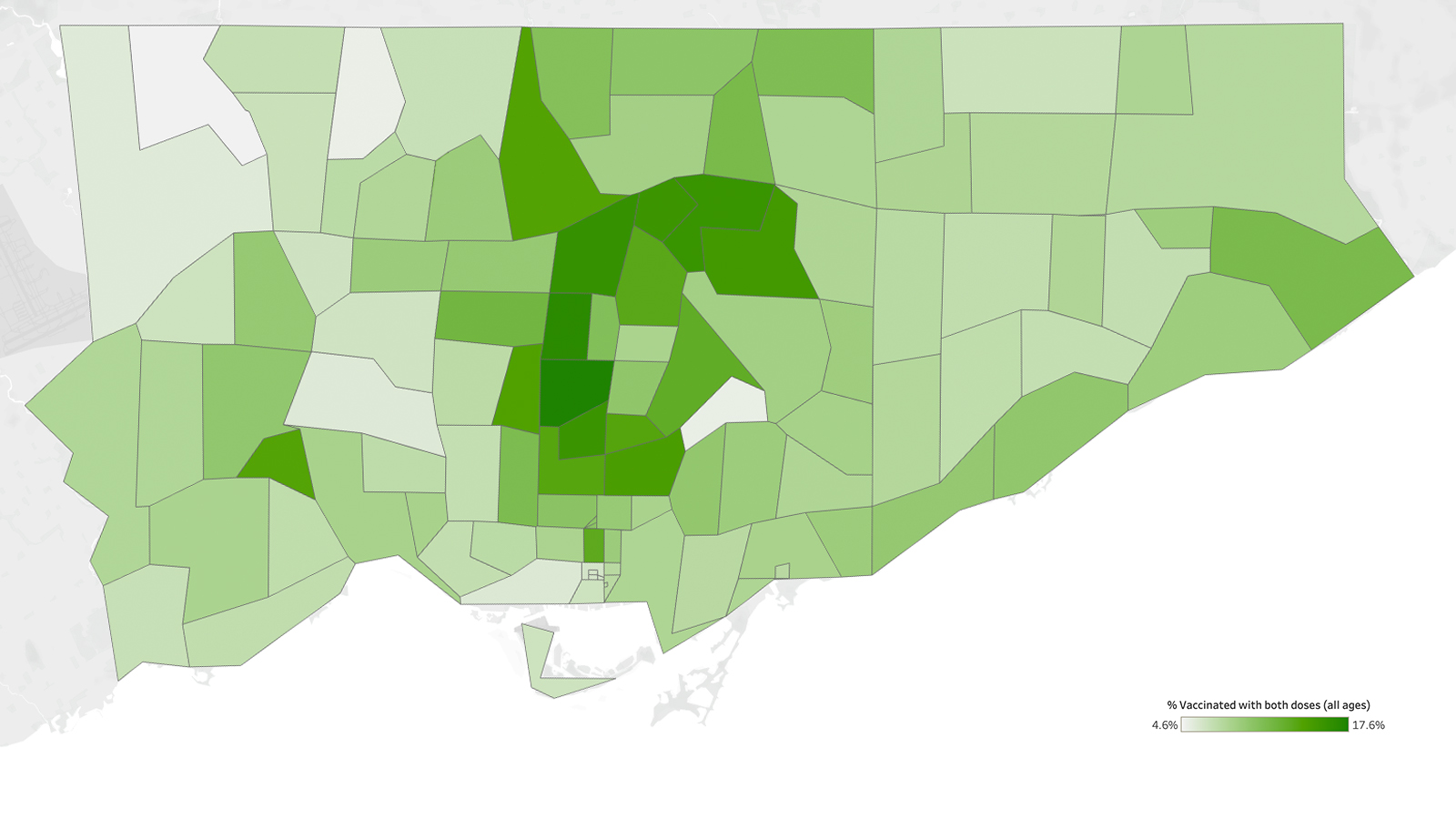

The five postal codes with the highest vaccination rates are located in Moore Park, Forest Hill, Forest Hill South, the Kingsway, and Rosedale—wealthy neighbourhoods with few COVID cases, all of which have vaccination rates over 21 percent. None of the numbers include individuals living inside long-term care homes.

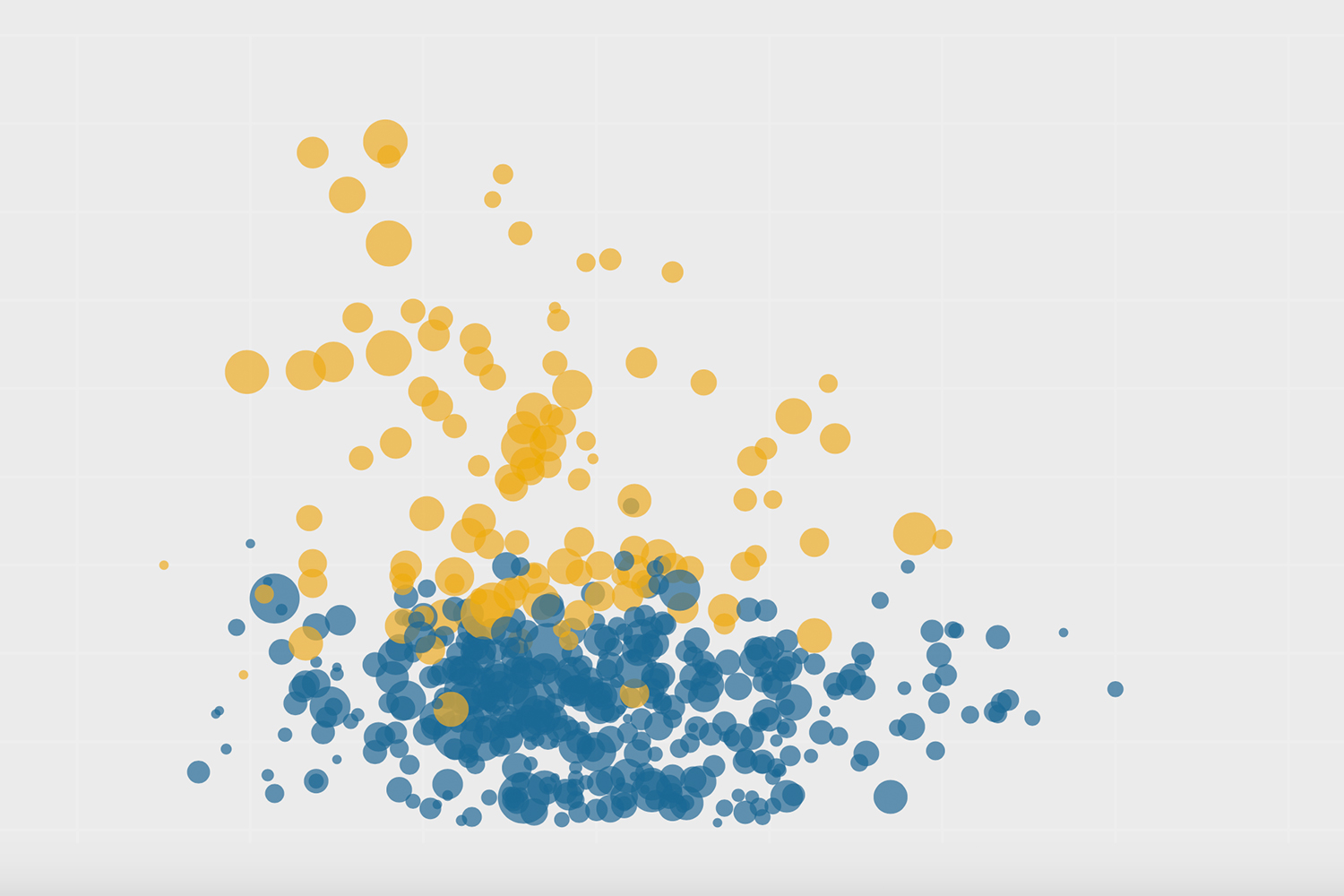

The numbers reveal a map of vaccinations that is a near mirror image of COVID hospitalizations and deaths. The Torontonians least at-risk are being vaccinated. Those most at risk are not.

Many of the neighbourhoods with the lowest vaccine rates are in Toronto’s northwest. That area, with large numbers of racialized people and immigrants, has had some of the highest COVID hospitalization and death rates in the city throughout the year-long pandemic.

Analysis by The Local last month found that in the five Toronto neighbourhoods worst-hit by COVID, all in the northwest, there were no pharmacies offering vaccines. The five neighbourhoods with the fewest infections had 12. The province has since expanded the program, adding some pharmacies in these neighbourhoods.

But the disparity in access to vaccines remains stark. In the postal code M3N, the area around Jane and Finch with a population of 42,000, there are just six pharmacies or clinics offering the vaccine within a 3 kilometre radius, four of which opened after March 31. In M4T, the wealthy Moore Park neighbourhood of 10,000 at Mt Pleasant and St Clair, there are 29 pharmacies offering vaccines within the same radius, plus a mass vaccination site in the works.

Michelle Dagnino, director of Jane/Finch Centre, says the vaccine rollout has failed to reach the seniors and low-income essential workers in her community. “We have an aging demographic, many of whom do not even have a device connected to WiFi in their home,” says Dagnino. “In a community like Jane and Finch, you cannot have just this approach of ‘Well, if we start up a website and put out some information to the news bureaus, people are going to be able to sign up.’”

“Most folks in these communities feel that they’ve always been left to the last and left behind,” says Cheryl Prescod, Executive Director of Black Creek Community Health Centre. “So if they’re not able to get to a vaccine site because of transportation issues or work schedules or childcare issues or all of those barriers that people living in poverty and dealing with stressful life situations have, then the likelihood of them getting to that vaccine site is so low. And it’s up to us as health care workers to figure out how to get it to them.”

Dagnino says that many of the workers she talks to simply cannot afford to take time off to get vaccinated and, without paid sick days, fear getting mild symptoms from the vaccine that could lead to more lost time. Last week, she got a call from a woman who regularly uses the centre’s foodbank program. Her husband works at a large food manufacturing plant where there have been several outbreaks. “She has her elderly mother living with her. And she has two young children who she’s kept back from school because they’re trying to minimize the risk as much as possible to their husband, who needs to go to work everyday because they rely on his income to pay their rent and to eat,” says Dagnino.

The husband is now eligible for a vaccine. “But they were afraid to have him take a day off to get the vaccine, and they were afraid that he would have some symptoms that could keep him home.”

In the first weeks of the rollout, Dagnino says she heard some questions around the safety of vaccines. But she thinks the issue of vaccine hesitancy has been overblown. “I think it’s a way of absolving some responsibility around the rollout,” she says. “I have heard very, very few people say that they are hesitant about the vaccine.”

This postal-code specific data arrives as Ontario’s medical community is sounding the alarm about the third wave with new desperation. As of Tuesday, there were a record 510 patients in Ontario ICUs. Doctors have taken to television and social media to share stories of young essential workers in their ICUs, and ambulances are bringing patients from Toronto’s overcrowded hospitals to beds as far away as Kingston and London.

Vulnerable essential workers are driving this third wave and bearing the brunt of its impact. A recent study led by Dr. Zain Chagla, an infectious disease specialist with McMaster University, showed a 50 percent growth rate in COVID variants of concern (VOCs) in the Toronto and Peel neighbourhoods with the highest percentage of essential workers, compared to just 18 percent in neighbourhoods with the fewest essential workers. Notably, that study was done in February and March of this year—when Toronto and Peel were essentially in lockdown, but essential workers continued to do their jobs without paid sick days, as they continue to do today.

“A 70-year-old who can stay home has a considerably lower risk than an essential worker who is 35 or 40,” says Dr Peter Juni, a member of Ontario’s Science Advisory Table. In late February, Juni was one of the authors of a brief that showed that prioritizing Ontario’s most vulnerable postal codes would prevent more infections, hospitalizations, and deaths than an approach based solely on age. “What we need to now avoid is the (scenario) where those who suffered the burden are not among those who get the vaccine,” Juni told The Star at the time.

We are now in precisely that scenario.

The province’s vaccine distribution strategy emphasizes age above all else, even as it has long been clear that a person’s risk level is directly tied to their postal code. That approach has led to vaccination sites with slots unfilled, and health officials rapidly lowering their age limits, even as the hardest-hit neighbourhoods remain largely unvaccinated.

In recent weeks, health officials have moved to try to address some of the vaccine inequities reflected in these early numbers. In Toronto, some clinics have already begun lowering age limits for people from priority neighbourhoods. Last week, a clinic run by Humber River Hospital opened at Downsview Arena, and on Monday the city opened a mass vaccination site at Downsview Park, both in the city’s northwest and both offering vaccines to anyone over fifty from a high-risk postal code. This week, John Tory said the city is working on a plan to bring mobile vaccination teams to high-risk neighbourhoods.

Joe Cressy, chair of Toronto’s board of health, points to the fact that the city recently began offering transportation to seniors to get vaccinated, as well as a multilingual outreach campaign that launched this Monday. “The entire community mobilization vaccine plan is predicated on trying to end every barrier to access,” says Cressy. “So long as supply is limited, vaccines should be targeting the most vulnerable as quickly as possible. That is not only how you save the most lives, but that is also how you bring this pandemic to the end soonest.”

On Tuesday, the province announced changes to Phase 2 of its vaccine rollout. Soon, people over the age of 50 in hot-spot neighbourhoods will be able to register for a vaccination. The province also moved up its timeline for vaccinating essential workers, by two weeks, to the middle of May.

Those modest changes don’t go anywhere near as far as some experts think is necessary.

“We need to stop passing on vaccine distribution on a per capita basis,” says Juni. “We need now to move into these hot spots, need to work heavily with the community organizations, and need to make sure that we have enough vaccines, enough manpower, and a simple process to get those vaccines into the people’s arms that need it.” He suggests bringing vaccines to warehouses and factories in the northwest and Peel, places we know have had outbreaks. He also thinks it’s time to consider bringing down the minimum age for vaccination to 25 in hot-spot neighbourhoods.

Vaccinating people in these neighbourhoods is hard—far harder than simply lowering age limits across the board, bumping up the province’s per capita vaccination rate. We’ve seen similar patterns of vaccine inequality in large cities across North America, from Chicago to Washington to New York. But a vaccination strategy can’t work if it doesn’t reach the people who are getting sick.

A year ago, when the city first released neighbourhood-specific data about COVID-19, it was clear that this disease followed familiar patterns: a map of COVID infections could be superimposed, with striking accuracy, on maps of poverty, racialized populations, and even diabetes rates. The city’s COVID epicentres have remained constant throughout the first, second, and now the third wave. It’s long been known who is most in need of protection.

“I get very angry at our responses when we know better,” says Prescod. “We knew better.”

Now, with a third wave threatening ICUs and dangerous VOCs hospitalizing people in their thirties and forties, experts are saying we can’t afford to wait any longer to protect the most vulnerable. “We need to try to help get the fire under control where it’s needed. And that’s in these hot-spot neighbourhoods. And everybody will benefit from it. Everybody. The entire province will benefit from that,” says Juni. “It needs to happen within days.”

The Local’s ongoing vaccination coverage is made possible through the generous support of the Vohra Miller Foundation.