Last Friday morning, on the day Health Canada approved the Pfizer vaccine for children aged five to 11, tired health care workers and volunteers in puffy winter coats surveyed the gym at St. Francis de Sales catholic school with the practiced eye of vaccine-clinic veterans. The group was part of an army of organizers visiting gymnasiums and cafeterias across Toronto to lay the groundwork for a new kind of vaccine pop up—the school-based clinics.

Inside St. Francis de Sales, a catholic school at Jane and Finch, staff from Humber River Hospital, Black Creek Community Health Centre, and several members of the school community roamed freely through the empty corridors and classrooms, taking advantage of the PA day. The first stop was the gymnasium, the only space large enough to house a clinic for the school’s 370 students along with kids from four surrounding schools.

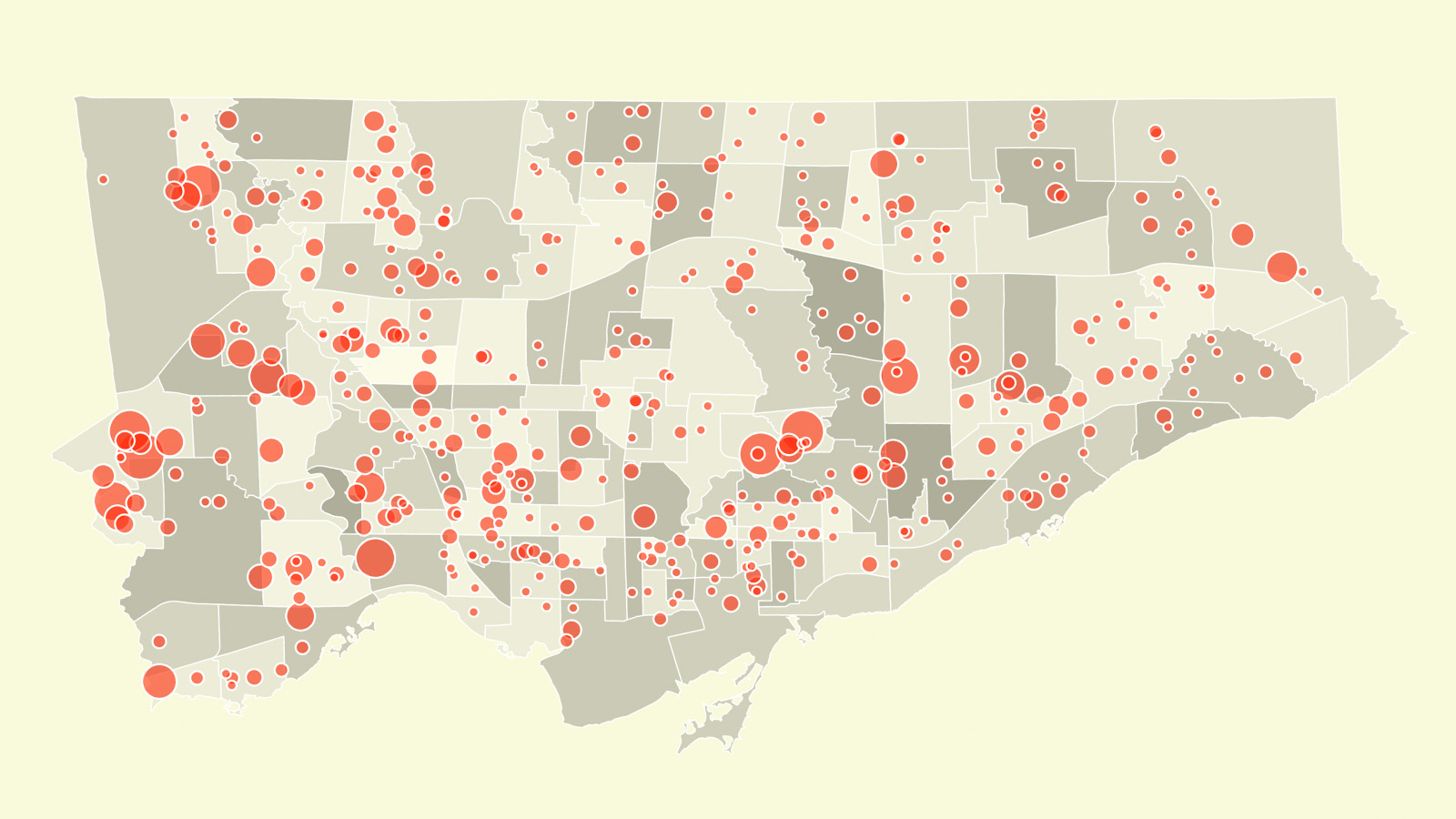

St. Francis de Sales would serve as the hub, while the other schools would be the spokes in a “hub-and-spoke” arrangement that is meant to give low-barrier access to the 1,550 students in the area. After a week, the clinic would migrate two kilometres north along Jane Street to Brookview Middle School, another hub among several spokes. In all, the city says 55,000 children across 390 schools will be able to receive their COVID vaccines through 230 such clinics across 34 priority neighbourhoods.

If this all sounds sophisticated and orderly, that’s because it is. Unlike those springtime tent-in-the-park pop ups that felt raucous and random, school-based clinics promise to be the most refined and delicate version of a community-oriented response to the pandemic yet. They will also be the final act for the many workers and volunteers involved in the exhausting, now almost year-long campaign to bring vaccines to those most impacted by COVID.

School-based clinics are part of the Team Toronto Kids COVID-19 vaccination plan, a junior version of the broader immunization campaign, and one that the city says prioritizes schools in areas like Jane and Finch from day one.

“The principle is to vaccinate the most vulnerable as quickly as possible,” said councillor Joe Cressy, chair of Toronto’s board of health. “Rather than waiting to see the disparities emerge before adjusting, let’s try and stop those disparities before they even start.”

Practically speaking, what this means is that as vaccines for kids roll out this week, they won’t just be for those whose parents were able to book an appointment at one of the city’s mass vaccination clinics or retail pharmacies; low-barrier school clinics located in priority neighbourhoods like Jane and Finch will also go live at the same time.

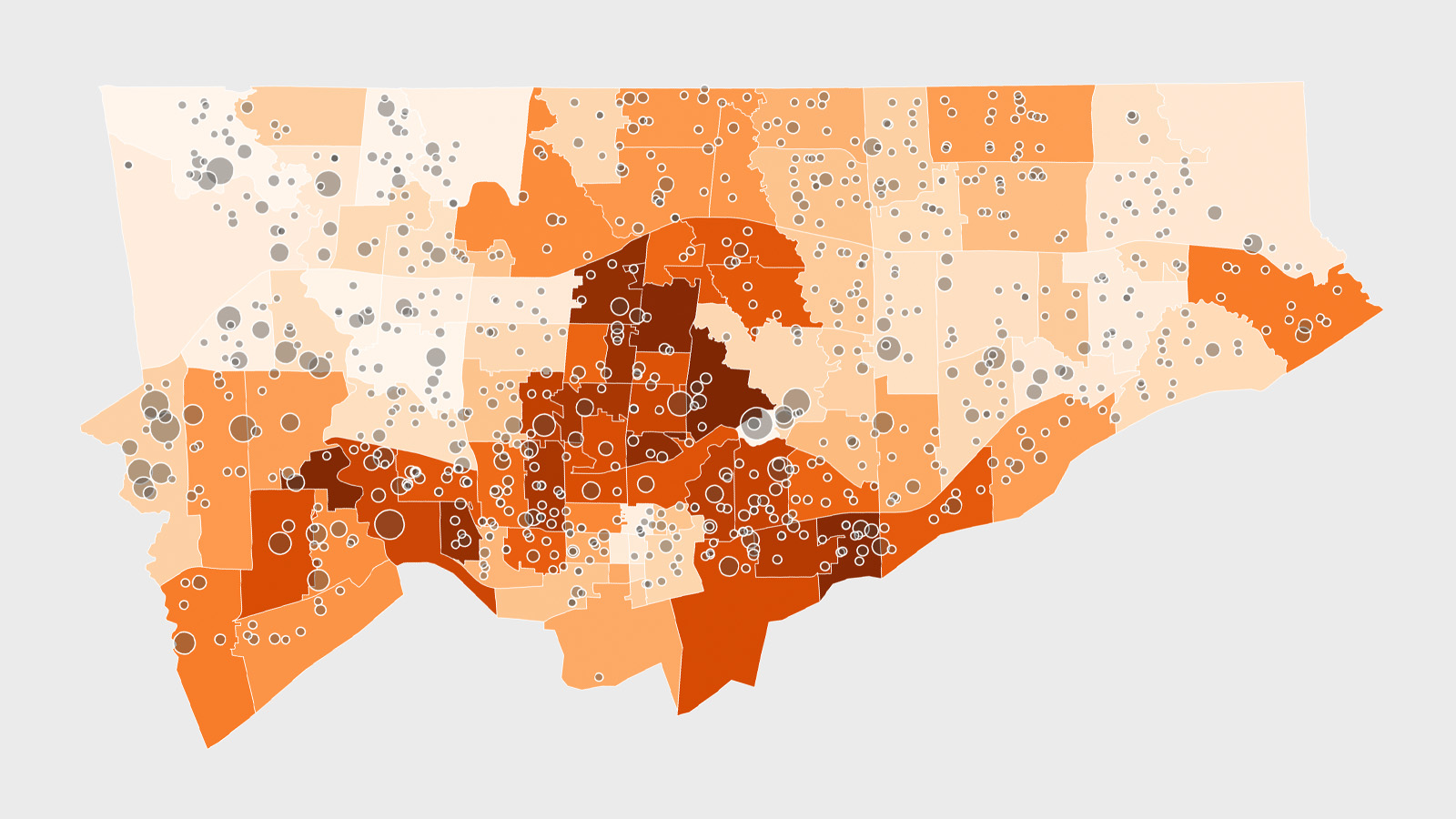

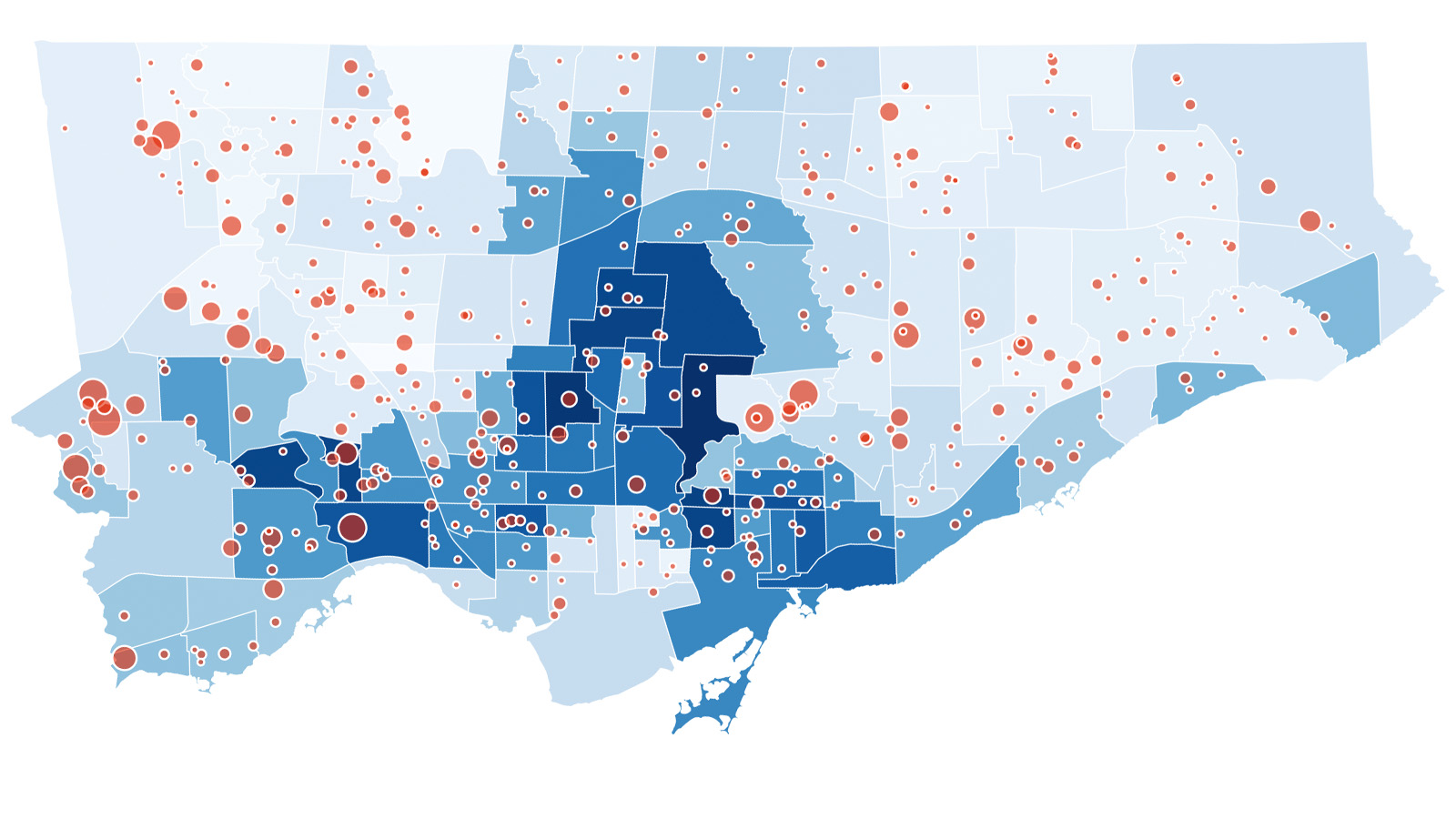

To fully appreciate the importance of this move, we need only look back some seven months, when data revealed that first doses were missing COVID hot spots—precisely the places they were meant to help the most. The city’s thick socio-economic gradient had filtered out those without the time or digital resources to chase down coveted appointment slots, and market and political forces had conspired to ensure that pharmacies in low-income neighbourhoods were excluded from the COVID vaccine business. A major shift in strategy ensued, with pop-up clinics as the countermeasure.

“This time we’re not waiting until the second or third or fourth week of implementation, we’re trying to get ahead of it right out of the gate,” said Cressy. Allocating vaccine supply to school clinics in high-needs areas is an important first step. It’s also an easy step since there’s ample supply of the vaccine to go around, which wasn’t the case in early spring. The harder part is getting the details right on the ground.

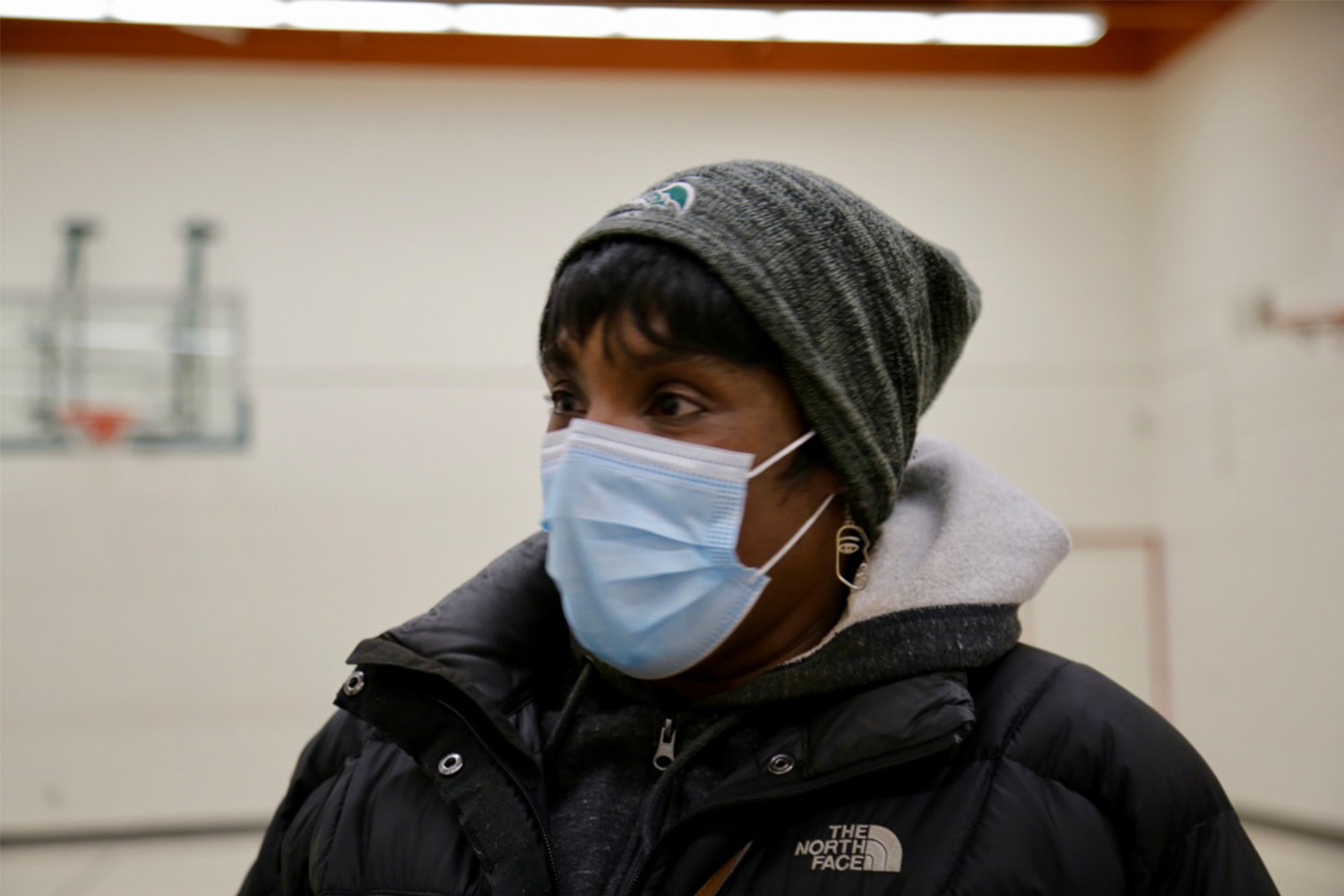

When the first pop-up clinic came to Jane and Finch in mid-April, Tamara Largie jumped at the opportunity to get involved. As a volunteer, she greeted residents and helped manage the long line that wound along Tobermory Drive. Largie has lived at Jane and Finch since arriving from Jamaica at the age of three. Now, as the parent of an 11-year-old at St. Francis de Sales and chair of the school’s parent council, she was among the small group gathered in the school’s gymnasium to orchestrate one of Toronto’s first school-based clinics for the newly approved vaccine.

“One thing I can say about this neighbourhood is that a large amount of our families are essential workers,” said Largie. “And that’s why timing of clinics is very important. We have to have weekends. We have to have evenings and mornings, flexibility for our families.”

The clinic, the team agreed, would operate from 1:00 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. on Thursday and Friday, and 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. on Saturday. Having clinic hours during school is a sensitive topic, since some parents fear losing control over how, when, and even whether their child gets vaccinated. Largie thinks that most parents will likely want to come after school with their children, but having clinic hours overlap with school hours will give some busy parents the option of consenting to their child getting the vaccine in their absence.

“Making sure parents can read thoroughly and understand these consent forms will be key,” said Largie. This means ensuring that the forms are easy to understand, and that proper language supports are offered, particularly for the area’s large Spanish and Vietnamese-speaking residents.

Parental consent forms will also be important in other ways. “We have a lot of nurses and PSWs in this community, and that’s a heavy workload, so I can anticipate a lot of older siblings who are 17 or 18 bringing their younger siblings,” Largie said. Others will be accompanied by a grandparent who does the regular after-school pickup. Having the parent sign the consent form ahead of time will help. And if that feels too complicated, parents will have the option to bring their children in on Saturday.

Joining Largie in the huddle that day were Michelle Westin from Black Creek CHC and Upasana Saha from Humber River Hospital, both of whom have organized dozens of pop-up clinics since April—seasoned veterans on the pandemic timescale. Like clockwork, they proceeded methodically through a series of operational issues, zeroing in on not just the physical, but also the social barriers that might stand in the way of people getting jabbed.

As the morning wore on, more and more details got hammered out. The music room would serve as a mini clinic for children with special needs who might be overwhelmed by the over-stimulating environment of the large gymnasium. Vaccine stations would be more spacious than usual to accommodate parents and siblings tagging along. Chairs in the aftercare area would be arranged in clusters instead of single rows. There would be just enough security in case anti-vaxxers show up, but not so much that they deter local residents.

According to Largie, the most important thing is to ensure that they have an inviting setting, and that means paying attention to details. “We just want the environment to be warm, because these vaccines are very important,” she said. “All clinics will look different based on the neighbourhood because each neighbourhood is designed differently. […] Finding Jamaican doctors, finding Black doctors, finding Spanish speaking nurses—these things are vital to a good vaccine clinic, especially in our area.”

For Upasana Saha, who leads Humber River Hospital’s pop-up efforts, school-based clinics represent the finish line in a vaccine marathon that has touched nearly every aspect of her professional and personal life.

Saha has other duties at the hospital and within the community. She’s working on her PhD. But for the last year, all of that has been shoved to the side in the all-consuming push to get the city vaccinated. “I think when you do vaccines, you really can’t do anything else,” said Saha. “Everything else kind of falls to the wayside.”

At St. Francis de Sales, Saha and her team have had to work quickly in order to launch on day one of the city’s junior vaccine campaign. That day in the gym, clinic furniture still needed to be ordered and delivered, posters and notices needed to be designed and finalized, clinical staff needed to be trained on how to draw up the pediatric dose, vaccines needed to be received and properly stored.

Even with all the stress and ambiguity that come with running pop ups, Saha acknowledges that it’s also been an exhilarating experience. “The silver lining through all of it is my learnings and the people that I have met,” she said. “I don’t think I would have had those experiences if it wasn’t for the pandemic and for the role that I played in supporting the different efforts.”

Saha is part of a special breed of pandemic workers—a kind of special forces that can be deployed anywhere, at any time. There’s plenty of field work, in addition to Zoom calls. On top of that are the irregular clinic hours, demanding evening and weekend availability, and new locations each week. “You go home really late, firstly, and then you just want to, you know, close your eyes,” she said. “You just want to rest. And then it’s just rinse and repeat the next day.”

When the school clinic opens on November 25, Saha will be there in the gymnasium, making sure things run smoothly and watching what she hopes is the first day of Toronto’s final mass vaccination campaign. For Saha, and for many others in her line of work, bringing vaccines to places like Jane and Finch is gratifying, but it’s also exhausting. And if there’s a personal stake in all of this, it is to put an end to this pandemic so that they too can move on with their lives.