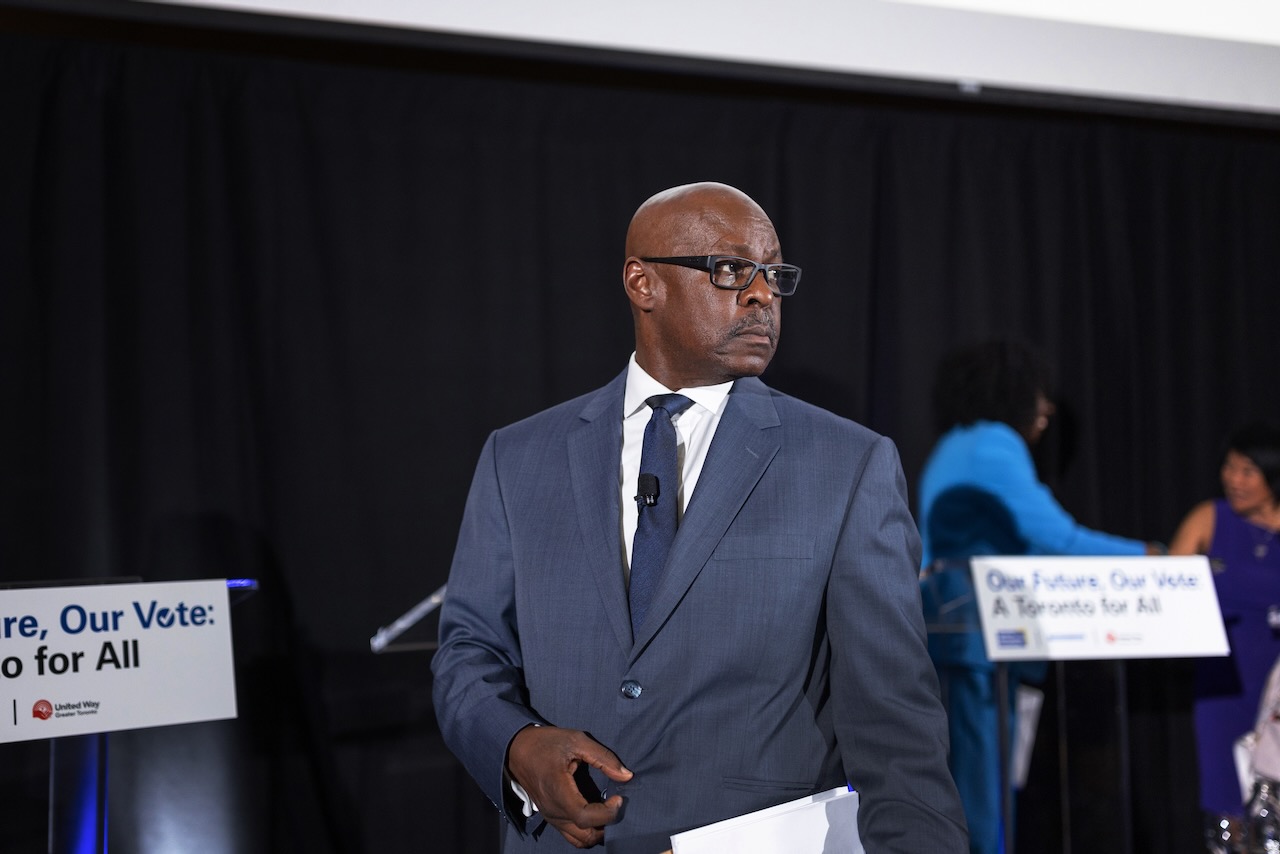

When Lisa Murray first met Mark Saunders, she thought he was everything a police officer should be: dignified, compassionate and responsive. It was 2015, and Murray worked as a manager at Toronto Community Housing, where reports of gang activity were commonplace. Whenever there was an issue and the police were called, Murray says the newly minted police chief offered the agency whatever support they needed.

One time, Murray says she remembers Saunders comforting a mother who had lost her son to gang-related violence. “After about 45 minutes, someone sort of tapped him on the shoulder and said, ‘Chief, we have to go, we have a meeting back at the office.’ And he said, ‘move the meeting. I need to be here right now.’”

The memory stayed with her. So, years later, when a friend called her up, told her Saunders was running to become Toronto’s next mayor, and asked if she wanted to join the campaign as a volunteer, Murray had just one answer: “Yes.”

To Murray, what makes Saunders the most qualified person to lead Toronto is his past. “He was a police officer for 38 years,” she says. “That means every day, he was making hundreds of individual decisions that had immediate, real consequences.”

Never Miss a Story

Sign up to get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

How voters see Saunders is a Rorschach test, skewed almost entirely by their own perception of the police. Running on a platform almost singularly focused on public safety, the Saunders campaign is clearly seeing his long career in policing as a strength. However, what makes him stand out in the crowded field of candidates jockeying for the city’s top job also works against him in the race. Saunders’ image as a competent career policeman who will excel as mayor only works on people who’ve either had good experiences with the police, or who have positive associations with them despite having never encountered them. This rosy perception could not be farther from the truth for some members of Toronto’s Black, Indigenous, unhoused and LGBTQ+ communities, or anyone else similarly standing at the forefront of the city’s fraught relationship with the police.

“There’s no question that some voters do get attracted to a law and order candidate,” says John Sewell, member of the Toronto Police Accountability Coalition, and a former mayor of Toronto. “But you know, the problem with Saunders is that he’s been a police officer for basically the whole of his adult life. He’s heavily infused with police culture, which is sexist and racist and violent.”

In 2015, when Saunders took on the role of Toronto police chief, he became the first Black man to hold the title. The appointment was historic; Saunders also became the second Black man to lead a police service in Canada. But how Black residents of the city feel about his tenure has been divided.

Sam Tecle, a sociology professor at Toronto Metropolitan University, says some residents of the city hoped that Saunders would be sympathetic to the experiences of Black Torontonians at the hands of the police. Instead, “Saunders was even more so like a company man,” says Tecle. “He was a defender of the status quo. So rather than any kind of modicum of change, it was just more like a deeper entrenchment of the same.”

Saunders’ seeming reluctance to acknowledge the significance of his appointment rubbed community members the wrong way. In 2015, Saunders said the historic feat resonated with him after his son pointed it out to him. “He said, ‘Dad, that’s history,’” the Toronto Star reported.

“Being black is fantastic (but) it doesn’t give me super powers,” Saunders said at a news conference that year. “If you’re expecting that all of a sudden the Earth will open up and miracles will happen, that’s not going to happen.”

“I think it was a way of him signalling, I think, to his supporters that he wasn’t going to make race an issue,” says Neil Price, a community researcher and writer hired by Toronto Police to study carding in 2014. “He was trying to position it as something that was a bit of an afterthought, and therefore, diminishing its importance.”

Then, the Earth did open up. In the summer of 2020, following the murder of George Floyd, calls to defund the police could be heard around the world. Residents gathered in the streets and asked politicians to reallocate funding from bloated police budgets and invest them in social service programs. Activists decried the police for brutality against communities of colour, corruption, and a lack of accountability. Shortly after the movement gained global momentum, and three days after Saunders took a knee at an anti-Black racism protest, he announced his retirement as Toronto’s police chief, citing a desire to spend more time with his family. Once again, Saunders was handed a historic opportunity to transform the police force but he chose a different path. (Saunders declined an interview with The Local through his media representative, but provided written answers to questions via email.)

Instead of bridging a divide, many say Saunders’ ambivalence alienated him even further from the community. Black Torontonians say they weren’t looking for miracles or a saviour—they were looking for someone in a position of power to understand how unfairly the decks had been stacked against them, in particular when it came to issues of policing and criminal justice. A November 2018 report from the Ontario Human Rights Commission indicated that “between 2013 and 2017, a Black person in Toronto was nearly 20 times more likely than a White person to be involved in a fatal shooting by the Toronto Police.”

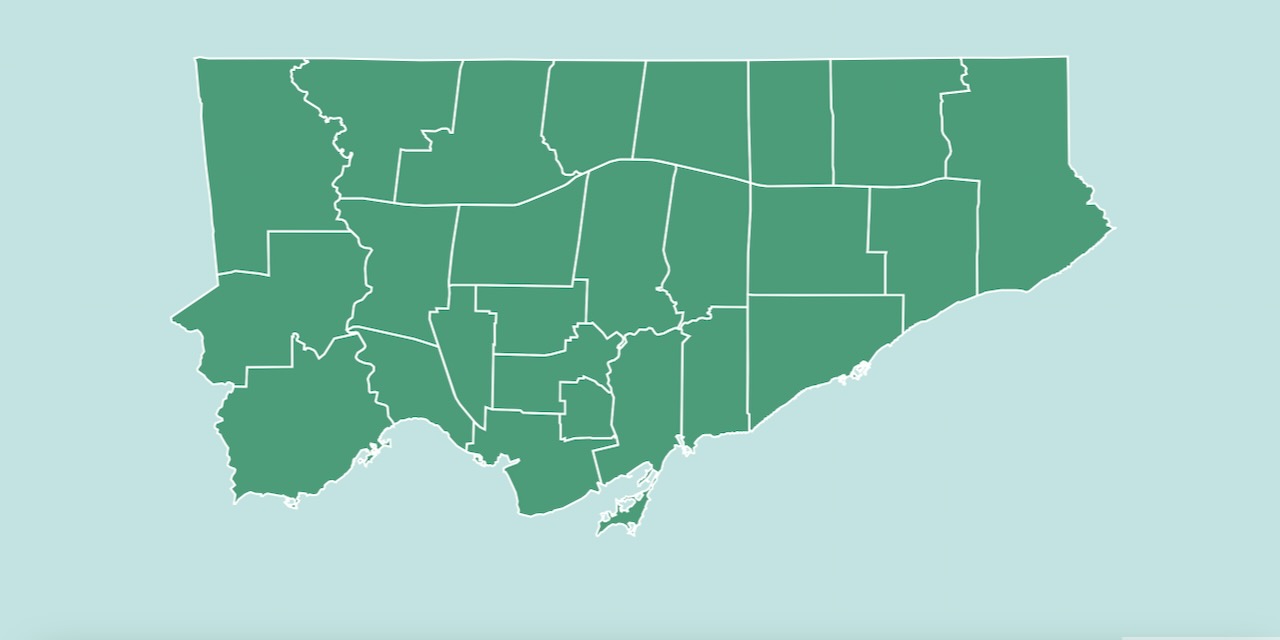

Even before calls to defund the police, Black residents of the city always had a fraught relationship with them. In 2014, the police board contracted Price to conduct a study about carding, the controversial practice once used by Toronto Police Services to stop and probe individuals, often without apparent reason. Price and his organization, Logical Outcomes, surveyed 400 community members across 31 Division (spanning north Etobicoke and some of western North York) in order to determine community satisfaction with policing. The study found that, in general, the level of trust in the police was low and many participants expressed negative views regarding the police. For example, a large number of respondents believed that police regularly racially profiled them and abused their power. “One of the findings that really shocked me was even in instances of emergency, many people would prefer not to involve the police. [This] led me to think that there were people who probably needed support, but wouldn’t call for it and were probably living with personal injury or under threat at times,” says Price. While research by the Toronto Foundation found last year that Toronto police remains one of the most trusted social institutions in the city—well above the school system, the courts, city hall, and local media—confidence in the police remains lower among Black residents of the city.

Saunders’ tenure largely perpetuated the status quo. Community activism and investigations by the media at the time revealed Toronto officers stopped and documented, or carded, Black and brown people at disproportionately high rates. When Saunders was appointed in 2015, he said he would not stop carding because it would lead to a rise in crime. In a statement shared with The Local, Saunders noted that he does not support random carding (which he distinguishes from carding “led by intelligence”). “I never have and never will. I do, however, believe that policing must follow evidence,” he wrote.

That summer, Andrew Loku, a 45-year-old South Sudanese man experiencing a mental health crisis, was shot dead by a Toronto police officer. Members of Black Lives Matter camped outside police headquarters for weeks, calling for the officer responsible to take accountability. In that time, Saunders never met with them.

Later in his tenure, he was criticized for his handling of the Bruce McArthur investigation, and for statements that felt like victim blaming to LGBTQ+ community members. Following the disappearance of several men from Toronto’s Gay Village, residents feared that there was a serial killer responsible. Saunders publicly denied the fears, and in an interview with the Globe and Mail following McArthur’s arrest, said he might have been caught sooner if “people that knew him very very well” had come forward with information.

In a statement to The Local, Saunders said, “Regarding the McArthur case, I know there is a lot of hurt in the community because of that case. As far as my role, I think that at certain times, I spoke to the evidence, not the emotion being felt by the community and for that, I apologize.”

In the time since his resignation, the former police chief has worked as an advisor at Ontario Place, netting a yearly salary of up to $171,500 in the part-time role. Saunders also unsuccessfully ran for provincial office in Don Valley West last year. However, in his political resurgence, Saunders has relied heavily on his years as a police officer to prove to Torontonians that he is qualified to run the city, saying he will use “38 years of experience and knowledge of this city to lift it back where it belongs,” and not referring much to any other professional experiences. But the question is, will his past help or hurt him?

Now on the campaign trail, Saunders says his own experience as a Black man makes him more knowledgeable about the realities of racism than other candidates. “I understand racism and discrimination, probably better than a lot of the other folks running for mayor. It is ironic that I was police chief but am still followed around in some stores just because of the colour of my skin,” he wrote.

Despite Saunders’ emphasis that he understands the experience of marginalized communities, critics point out that the messaging of his campaign doesn’t indicate that. Saunders has conveyed to voters that this election is a choice between crime and chaos and law and order, spotlighting recent crime on transit and stoking fears about the city’s harm-reduction approach to drug policies; while public safety will inform how voters cast their ballot come June 26, it’s not as simple a choice as Saunders portrays it to be.

The sentiment Saunders is trying to evoke underscores a general fear that has permeated the city as a spate of seemingly random violence on the TTC has left more Toronto residents afraid of relying on public transit. Last December, The Toronto Star reported that 2022 was on track to be the most violent on transit since 2017, and recent city data shows that between January and May, major crimes on all Toronto transit systems (including TTC and GO Transit) rose by more than 24 percent. However, compared to 2019, Toronto is not seeing a clear spike in the most violent crimes—homicides and shootings have decreased. Despite this positive trend, residents’ fears are not entirely unfounded, as data shows there has been an upward trend in assaults and auto theft.

Once again, Saunders was handed a historic opportnity to transform the police force but he chose a different path.

Saunders has said he will provide police with more resources to crack down on auto thefts in the city. To address violence on the TTC, he has pledged to increase the number of Special Constables to at least 200 and provide additional equipment for them, including body-worn cameras. Both moves garnered him an endorsement from CUPE 5089, the union representing Special Constables, TTC fare inspectors and guards. But not from critics who say that Saunders’ promise to ensure law and order is a dog whistle, and will only stoke fear in marginalized communities. “It’s fearmongering,” says Tecle, the sociology professor at Toronto Metropolitan University, and will lead to the over-policing of communities of colour, members of the LGBTQ+ community, and more.

“We know more law and order means more police. We know it means there’s going to be more resources committed to removing us from the public,” says Tecle. “It’s more people like us in prison, in lockups, in detention or to be deported. That’s what we hear.”

See All 102 Mayoral Candidates

Candidate Tracker has fact-checked biographies and platform summaries for every name on the ballot. Also available in print at your local library.

Despite Saunders’ preoccupation with public safety, some are also criticizing him for making plans they feel are in direct opposition to it. In May, he announced that he would reverse the decision on bike lanes for Toronto’s busiest streets, including University Avenue, Yonge Street and Bloor Street West in Etobicoke. According to Saunders, the decision will help ease congestion and funnel funds towards other priority projects like TTC safety, mental health services and affordable housing. However, critics say, Saunders’ targeting of bike lanes is antithetical to his promise to promote public safety. “He doesn’t realize that making our roads safer for everyone helps with public safety,” says Robert Zaichkowski, a Toronto-based accountant and biking advocate.

Saunders’ constant sparring with frontrunner Olivia Chow over safe injection sites and naloxone kits has also been described as fearmongering. While Saunders has stated that supervised injection sites save lives, he has complained about their impact on families and residents who live near harm-reduction facilities. In campaign material released in April, he noted that he had spoken to many families that “keep naloxone kits in their homes because they are afraid of their children getting poked with unknown substances and needing to administer life-saving Narcan.” Saunders’ statements have ranged from stories about concerns parents might have about their children coming in contact with discarded needles to misinformation about drug transmission through touch. Gillian Kola, a public health expert, called the assertion “pure fiction” in an interview with the Toronto Star, noting, “It feels like [Saunders] is trying to use misinformation to create controversy and attention for his political campaign, and from a public health perspective, it is totally irresponsible.”

While the criticisms of Saunders’ run are resounding, the former police chief says the sentiments expressed online and from members of marginalized communities who criticize his tenure as chief are starkly different from what he hears when door-knocking around the city.

“What we hear at the doors is that folks are concerned about public safety, crime on the TTC, gang activity, school lockdowns and car theft,” he says in a statement. “Those are consistently the number one issues and people are relieved that someone with a background in public and community safety has the practical experience to help move Toronto in a safer, more stable direction.”

He points to his record as chief of improving accountability, transparency and citizen safety. While some have described his five-year tenure as “middling,” it was not without some success. In 2019, Saunders announced Toronto police’s plan to collect and analyze race-based data and information in 2020. In an opinion piece published in The Star the following year, Saunders said the service would analyze the data to “identify systemic racism and trends and to develop mitigation strategies and evolve training,” and lauded the strategy as one that would “fundamentally change how [Toronto police services] deliver policing.” In June last year, data collected in 2020 revealed significant, disproportionate use of force against Black Toronto residents, which prompted an apology from James Ramer, who was police chief at the time. By then, Saunders had resigned from the post, and didn’t address the findings of the data publicly.

Saunders also helped introduce body-worn cameras for all front-line officers, expanded use-of-force options like tasers and sock guns, and provided mental health training for officers, including on crisis de-escalation.

Saunders has run his mayoral campaign primarily on law and order, and it shows in his approach to other policies. While he has released plans to address issues like housing and gridlock in the city, his main selling point to voters is that he is the antithesis of frontrunner candidate Olivia Chow, making unsubstantiated claims that if Chow is elected, she will “defund and de-arm the police” (she has no mention of reducing police funding or power in her platform). He has criticized councillors like Bailão, Matlow and Bradford as being complicit in the city’s degradation. The story he tells voters is that he has had his feet to the fire, and he’s able to move Toronto forward, unlike his opponents.

While Murray considers herself the quintessential Saunders voter, crime is not top of mind for her. As a woman in her late 50s, newly retired, and living in a rental condo on Front and Yonge, Murray fears what would happen if rent prices ballooned over the next year. “I worry every day that I’m going to have to move because there’s no way I can afford to pay another $700 or $800 a month in rent. I just can’t. And I’m terrified.”

When asked what about Saunders gives her the confidence that he will be able to address the complex issues facing Toronto outside of crime, like housing affordability, Murray points to the same phrases that Saunders uses to describe himself—the speed and effectiveness he’s garnered over the years as a police officer, and a willingness to make tough calls in the moment. “A leader says, ‘we have to do this, this is the right thing to do,’” says Murray. “We can’t have this group think—no more committee meetings, and no more reports. It’s hard to make a decision, but we have to make a decision. And that’s what he does.”

Ultimately, there is no set way to foresee the outcome of Saunders’ race for mayor. For many, the decision to vote for him will rely first on their perception of the police, but also on their perception of where Toronto is going and what the city needs. If voters lean into the fear and alienation they feel from their city and fellow residents, then Saunders’ promise to “protect Toronto’s future” might strike a chord.