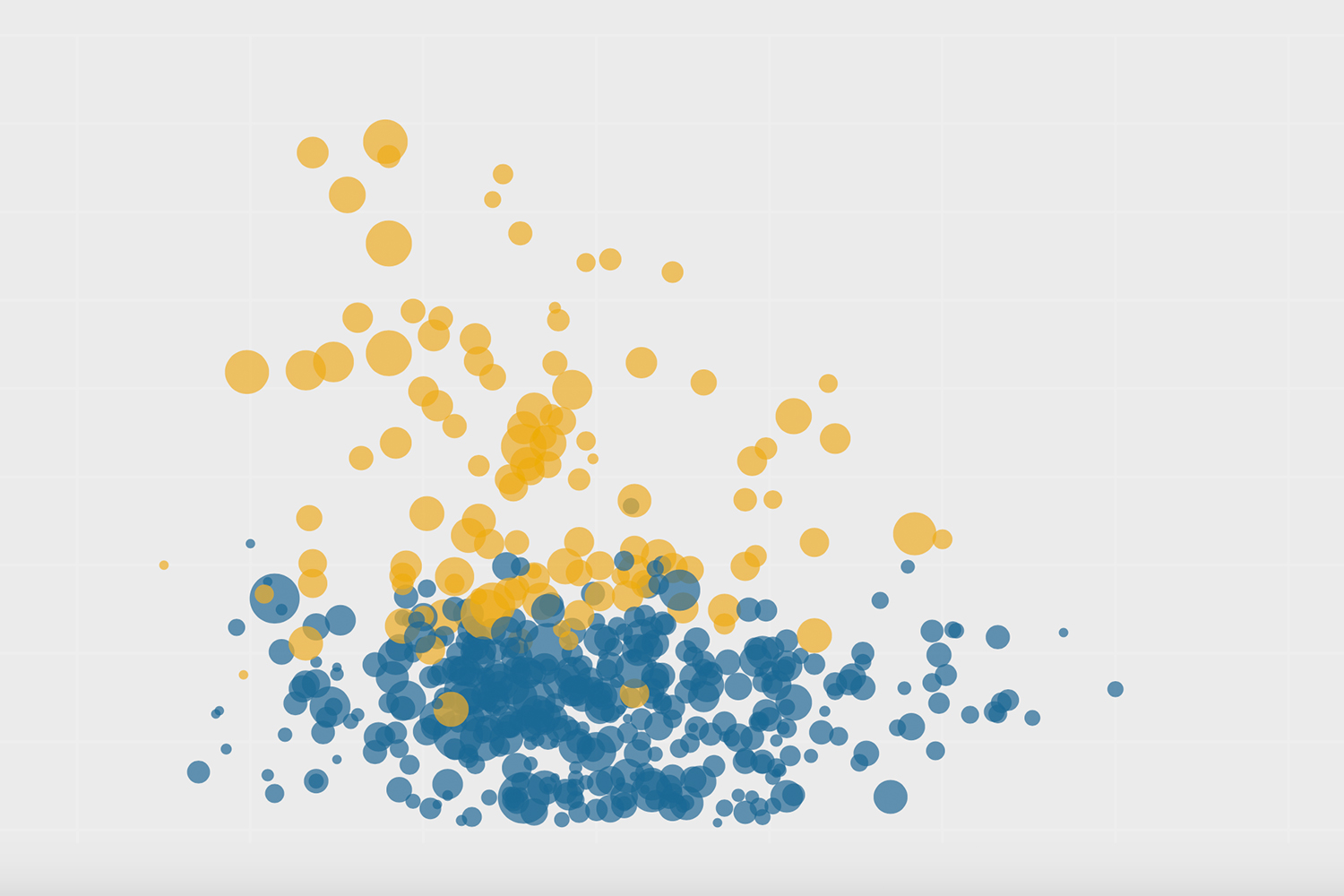

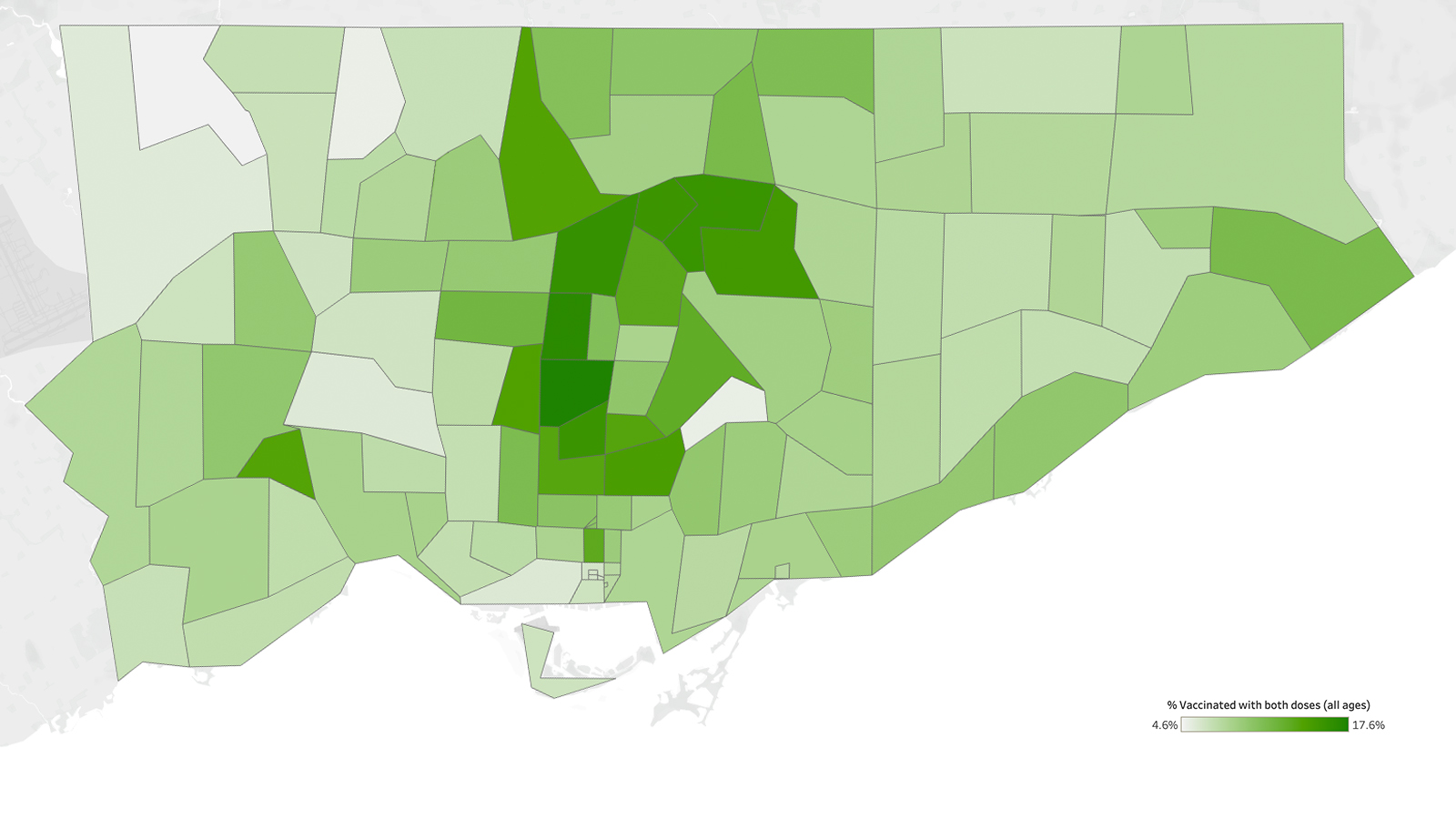

In the first days of the second dose rollout, a familiar pattern has emerged: the Toronto neighbourhoods most in need of vaccines are receiving them at significantly lower rates than the rest of the city.

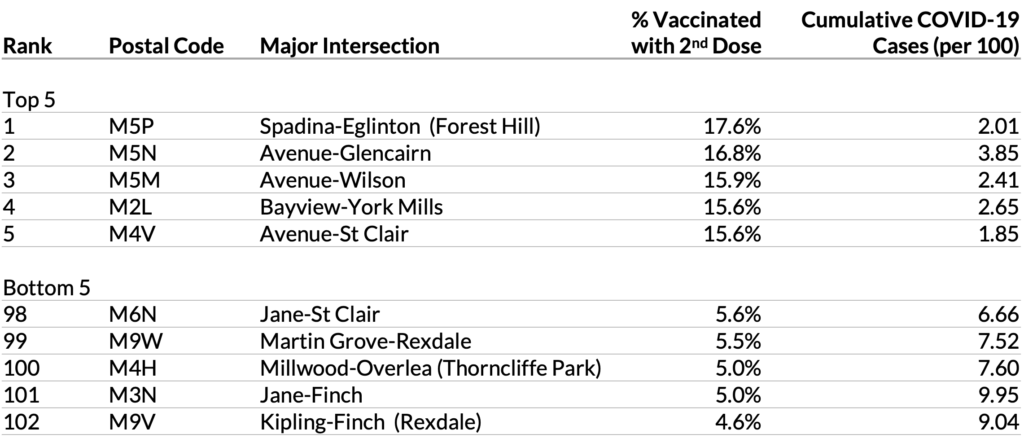

Data from the independent research group ICES reveals that second dose vaccination has raced ahead in wealthy neighbourhoods with low COVID rates compared to neighbourhoods with significantly more infections.

In affluent Forest Hill (postal code M5P), 17.6 percent of residents were already fully vaccinated as of June 7, the highest rate in the city and among the highest in the province. In Rexdale (postal code M9V), only 4.6 percent of residents had received their second dose, the lowest in all of Toronto. That’s particularly striking given the fact that Rexdale is among the top one percent of postal codes in the entire province for COVID infections since the pandemic began.

The distribution of second doses has a new urgency with the emergence of the Delta variant, which is both more contagious and less susceptible to protection from a single dose. Data from Public Health England found that one dose of Pfizer or AstraZeneca is only 33 percent effective against the variant. A second dose increased that protection to 88 percent.

While cases of the Delta variant are not yet available by postal code, according to Peter Juni, director of Ontario’s science table, the variant has shown up in the same high-risk neighbourhoods filled with essential workers that have long been vulnerable to COVID.

“It’s basically the same story as before,” said Juni. “It’s neighbourhoods with a large proportion of industrial workers, difficult living conditions, difficult economic situations, inability to stay home, and inability to isolate. That’s basically the risk factor profile of a neighbourhood that has either already experienced Delta, or could be challenged very close in the future.”

In a briefing in Brampton on June 9, Peel Medical Officer of Health Lawrence Loh warned that the Delta variant likely accounts for 30 to 35 percent of new cases in Peel Region and said that without timely second doses a potential fourth wave was brewing. Yet neighbourhoods in Peel are lagging behind when it comes to second doses. In Brampton, the median rate of second dose vaccination is a meagre 4.5 percent, roughly a quarter of the rate in Toronto’s most affluent areas, and significantly below the provincial average.

The second-dose numbers are partially a reflection of the inequality of the early days of the first vaccine rollout, when there were few pharmacies carrying the vaccine in at-risk neighbourhoods and a lack of pop-up clinics and other interventions designed to reach vulnerable populations. “Up until very recently, eligibility was based on when you got your first dose,” said Toronto board of health chair Joe Cressy. “So the people who got their first dose first, got their second dose first.”

Paul Das, an emergency room doctor at St Michael’s Hospital, has spent the last two months working to bring vaccines to Rexdale. Alongside the Rexdale Community Health Centre, he spent much of May setting up mass vaccination and pop-up sites, and has been doing more focused outreach in apartment buildings and schools since. Those painstaking efforts are about trying to help Rexdale catch up to some of Toronto’s other neighbourhoods. “All the work that we’re doing presently for getting people their first dose we should have been doing six weeks ago,” said Das. The delay getting the community the support it needed when the rollout began is now echoed in low second-dose numbers.

In order to break this chain, the city has launched what it calls Team Toronto Sprint Strategy 2.0. It has identified 18 postal codes, including M9V in Rexdale, deemed most at risk, where Cressy said 30,000 additional vaccine doses will be diverted this week. In addition to trying to reach the remaining unvaccinated populations, mobile and pop-up clinics in these areas are allowing residents to get their second dose after just three weeks of a Pfizer or four weeks of a Moderna first dose.

Cressy said the province has not explicitly increased the vaccine supply for hot spots, like it did in early May when 50 percent of doses were allocated to at-risk areas. And so Toronto is reallocating doses on its own at this point. “Locally we have divvied up the pie to provide an increased amount into those hot-spot areas,” said Cressy.

The province is allowing residents of Toronto, Peel and five other public health units to book their second doses earlier than previously scheduled. Starting June 14, residents in the seven regions who received an mRNA vaccine on or before May 9 will be eligible to book their accelerated second dose through the provincial booking system.

“The (provincial) acceleration of second doses in hot spots is good, but there should be a corresponding increase in supply,” Cressy added. That sentiment was shared by all GTHA mayors and chairs when they met last week.

Increased supply would enable cities like Toronto to bring more vaccines to targeted communities, instead of just relying on appointments booked through the provincial system. And whereas the provincial approach to accelerated second doses has a minimum interval of five weeks between mRNA doses, pop-up clinics operated by Toronto teams are already doing them in as short an interval as three weeks for Pfizer shots. This allows residents in high-risk areas who only recently got their first dose to get full protection sooner.

Health care workers in these communities emphasize that simply flooding these neighbourhoods with vaccine isn’t enough. “It’s not good enough that we keep having these mass vaccination clinics, we need an approach where we’re bringing vaccines to where people are,” said Safia Ahmed, executive director of Rexdale Community Health Centre. “We know that a lot of people in north Etobicoke have schedules that may not allow them to go to mass vaccination clinics and may be working beyond those hours.”

“Outreach and communication is really important in hot-spot neighbourhoods,” said Jen Quinlan, CEO of Flemingdon Community Health Centre. “For people to really understand and interpret all the complexity of what’s being shared around the priorities for the second dose, you need a clear local message. It’s been hard for us to respond to the contradictions that are coming down over the last week.”

Amid a flurry of government announcements around second doses last week, Flemingdon CHC held a few second-dose pop-up clinics. “People were a little bit confused,” said Quinlan. They asked: “Is this for me? Is this my time?”

With COVID rates sinking and overall vaccination rates rising, Peter Juni is confident that these efforts will be enough to close the gap if we don’t lose focus. “It’s very important to keep emphasizing that we need to vaccinate strategically,” said Juni. “That means protect those that are most vulnerable. If you don’t focus on that you will have a complete asymmetry.”

But the second-dose vaccination data is only the most recent reminder of the inequalities baked into the city. Throughout the pandemic, the same map has been replicated over and over and over again, with the same low-income, racialized neighbourhoods experiencing higher COVID rates and lower testing numbers, more hospitalizations and fewer vaccinations.

“That’s a symptom of larger health care inequality,” said Quinlan. And vaccinating a population won’t change that. “That inequality will still remain for things like mental health rates or diabetes rates or the other types of health care conditions that we’re trying to support.”

The Local’s ongoing vaccination coverage is made possible through the generous support of the Vohra Miller Foundation.