When the mass vaccination campaign began in early spring, wealthy neighbourhoods raced ahead in getting their first doses. The same pattern was repeated at the start of the second dose rollout in late spring. In both instances, countermeasures were implemented whereby additional vaccines and resources were pumped into “hot spots”—largely low-income, high-infection areas—to keep any disparity to a minimum.

Low-income neighbourhoods had help, while affluent ones didn’t need any. Middle-class areas, on the other hand, just sputtered along beneath the radar. These neighbourhoods are now home to more than half a million under-vaccinated individuals.

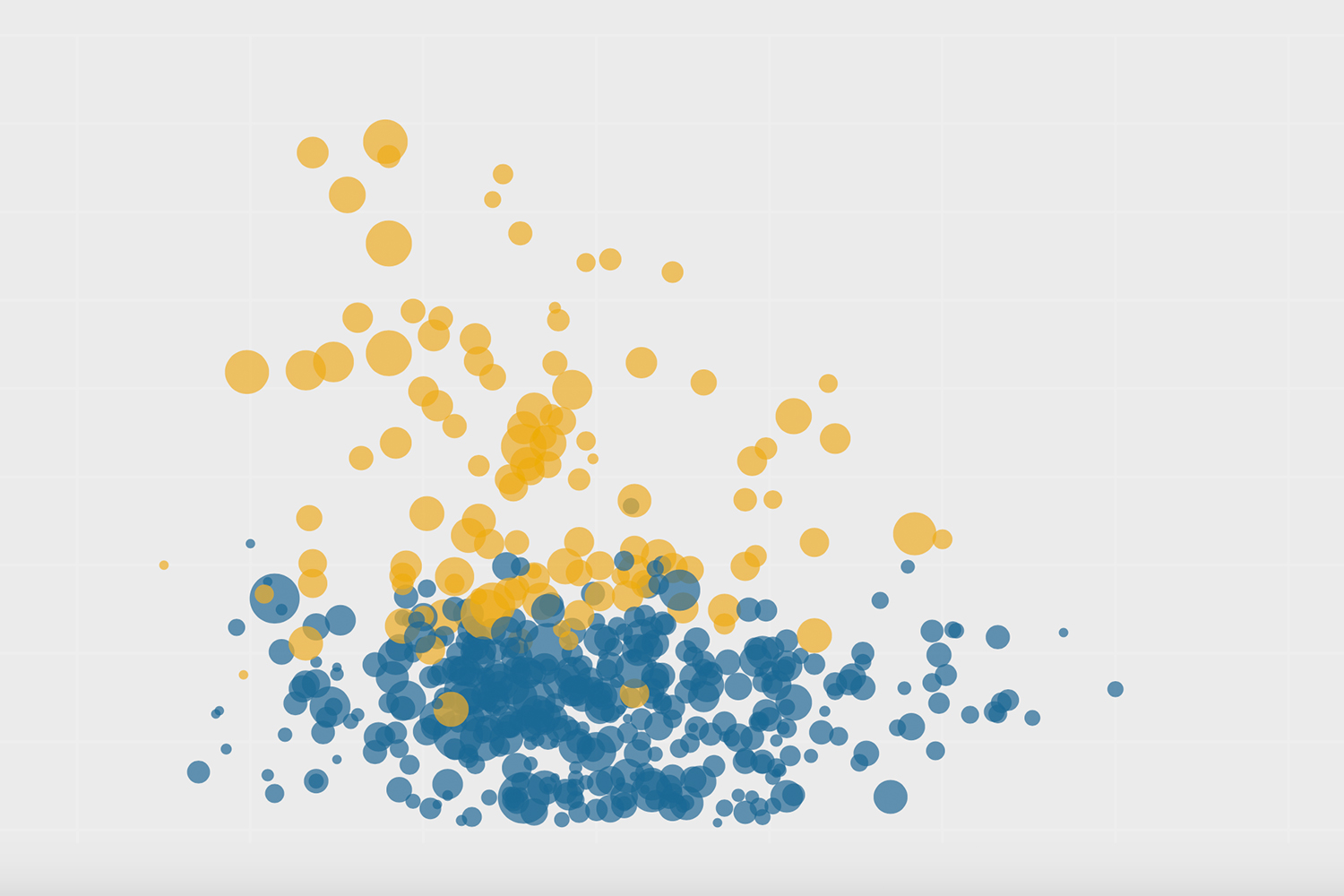

As of July 4, data from ICES showed that across Toronto, there were 600,000 people 12 years of age or older who were eligible for, but had yet to receive their first dose, as well as 700,000 people who had received their first but not their second dose. Of these 1.3 million under-vaccinated individuals, roughly 20 percent live in high-income, 40 percent live in middle-income, and 40 percent live in low-income areas (based on whether the average individual income of the postal code falls within the upper, middle or bottom third for the City of Toronto).

Distribution of Toronto’s Under-Vaccinated Population

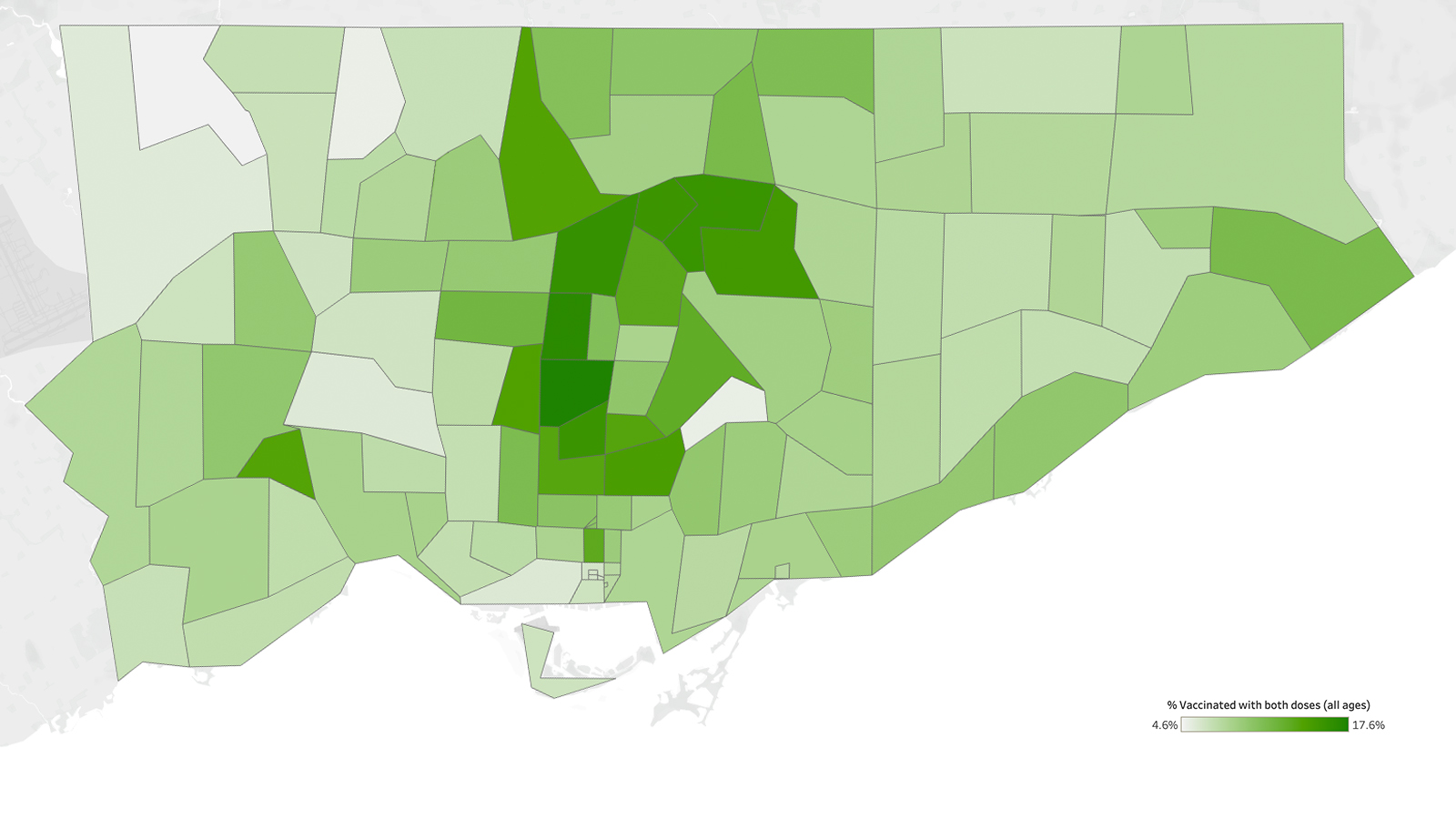

At this point in the vaccine rollout, when there is a need to zero in on pockets of the city where there’s still a large, under-vaccinated population, looking at the percentage of residents vaccinated may no longer be the most useful metric. While Thorncliffe Park (M4H) looks dire by the standard measure of progress, with just 58 percent of residents with first doses, it looks very different in terms of the sheer number of eligible individuals who haven’t been vaccinated. Due to Thorncliffe Park’s relatively small population and the fact that a large proportion of the community is made up of children below 12 years of age who are ineligible, less than 10,000 residents are under-vaccinated for first and second doses. At Yonge and Sheppard (M2N), that number is four times greater.

Middle-class neighbourhoods like Yonge and Sheppard are like “swing states” in an election. Their sizable under-vaccinated population means that they have a lot of sway over the final outcome of the vaccine campaign—whether Toronto hits 90 percent or some other measure of population protection. What happens in these neighbourhoods this summer will determine the city’s readiness for the uncertain, Delta-dominant fall season, when schools and other activities move indoors.

Sean Molloy leads North York General Hospital’s vaccine operation. His catchment area includes Yonge and Sheppard. According to Molloy, the neighbourhood is densely-populated, made up of mostly people under 40 years of age, living in condos. “There’s not a high level of COVID and there’s not a lot of access to vaccines either,” he said.

But what we’re seeing in middle-class areas like Yonge and Sheppard, said Molloy, is the result of a well-intentioned plan. “We designed the strategy to address those most at need, which I think was the right thing to do. But in the process what you have is this large swath of people that probably don’t have the same personal risk with their age, but likewise haven’t had the easiest access to the vaccine.”

With the majority of the general population now vaccinated, the calculus for who’s at risk and who’s not is quickly changing. Recent hospitalization and mortality data show that the biggest risk to your health is not being vaccinated. Whether or not you live in a “hot spot” with historically high rates of infection becomes irrelevant once you’re fully vaccinated. In this new world, places like Yonge and Sheppard (M2N), Don Mills and Sheppard (M2J), and Woodbine and Danforth (M4C)—middle-class areas with huge numbers of under-vaccinated people—need to be the new frontiers for the vaccine campaign. But they’re not.

Under-Vaccination in Toronto, by Postal Code

A month ago, the city launched Sprint Strategy 2.0 targeting two dozen postal codes for increased first and second dose uptake. None of them included the middle-class areas of concern. Last week, the city launched its Home Stretch Vaccine Push, a major blitz of areas in Toronto’s northwest where vaccine uptake continues to be low despite previous efforts. There’s been no word yet on when or whether such an approach could be expanded to areas like Yonge and Sheppard.

In the meantime, Molloy and his team continue with their modest efforts in the area: clinics at Earl Haig Secondary School and the Beth Emeth synagogue. There’s also a vaccine bus that visits different parks in North York. But with so many high-density condo towers, the area is ripe for a blitz-style campaign or perhaps a highly-publicized clinic at Mel Lastman Square similar to the record-setting events in Thorncliffe Park or Scotiabank Arena.

“When we’re going into these areas in North York, we’re still finding a lot of people who will take a first dose, and they’ll get it out of convenience,” said Molloy. “It’s not that they didn’t want it. They just didn’t really have an easy option of getting it.”

The Local’s ongoing vaccination coverage is made possible through the generous support of the Vohra Miller Foundation.