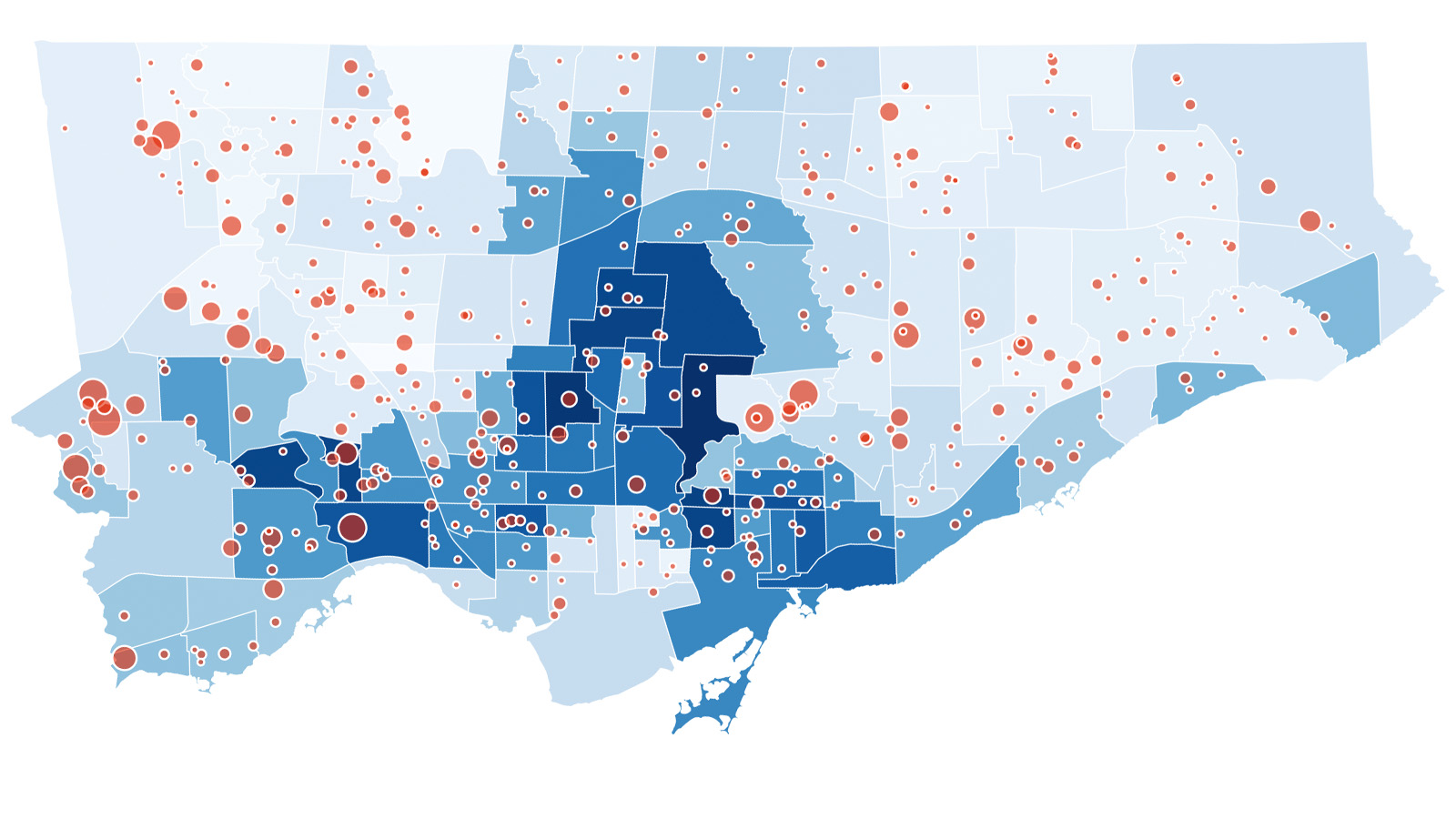

As school cases and outbreaks surge to record heights, new data sheds light on the state of Toronto’s kid vaccine rollout. City-wide vaccine uptake for those aged five to 11 currently stands at 29 percent—a remarkable feat considering the pediatric vaccine was only available to the masses two short weeks ago. However, those rosy overall numbers mask the reality that the communities where COVID is spreading most freely are among those with the lowest vaccine uptake.

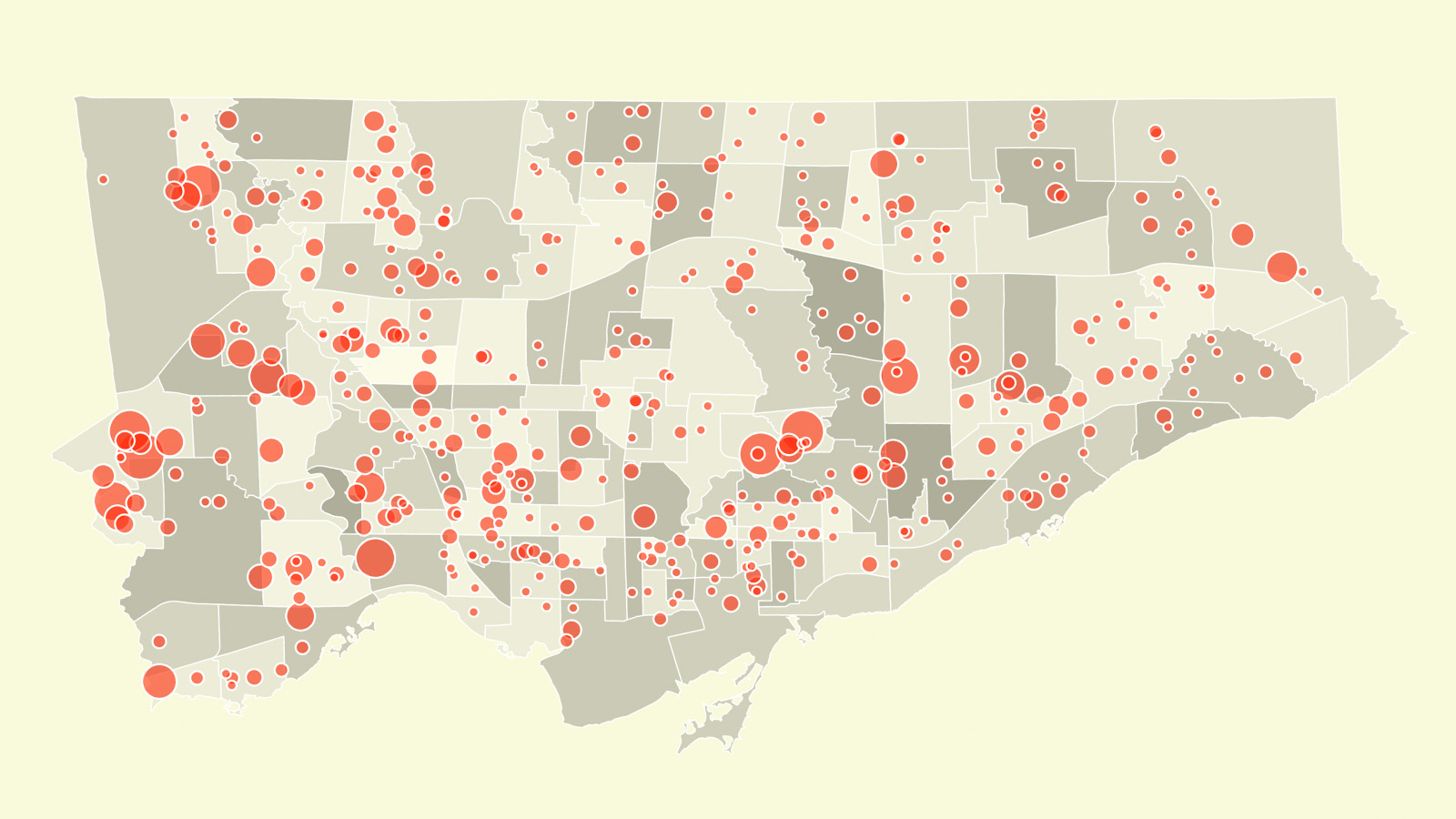

Analysis by The Local using unreleased data downloaded from Toronto Public Health’s website shows a wide disparity in vaccination rates for kids, with some Toronto neighbourhoods at nearly 70 percent vaccinated with a first dose and others sputtering along in the single digits.

Those rates break along familiar socio-economic lines. The most vaccinated areas are the affluent neighbourhoods of Leaside-Bennington, Forest Hill South, and Playter Estates-Danforth. As of December 5, between 65 and 70 percent of kids in those neighbourhoods had received their first dose—stellar progress over a short period of time. The areas with the lowest uptake are the lower-income, racially diverse neighbourhoods of Beechborough-Greenbrook, York University Heights, and Humber Summit. There, vaccination rates are at no more than 10 percent.

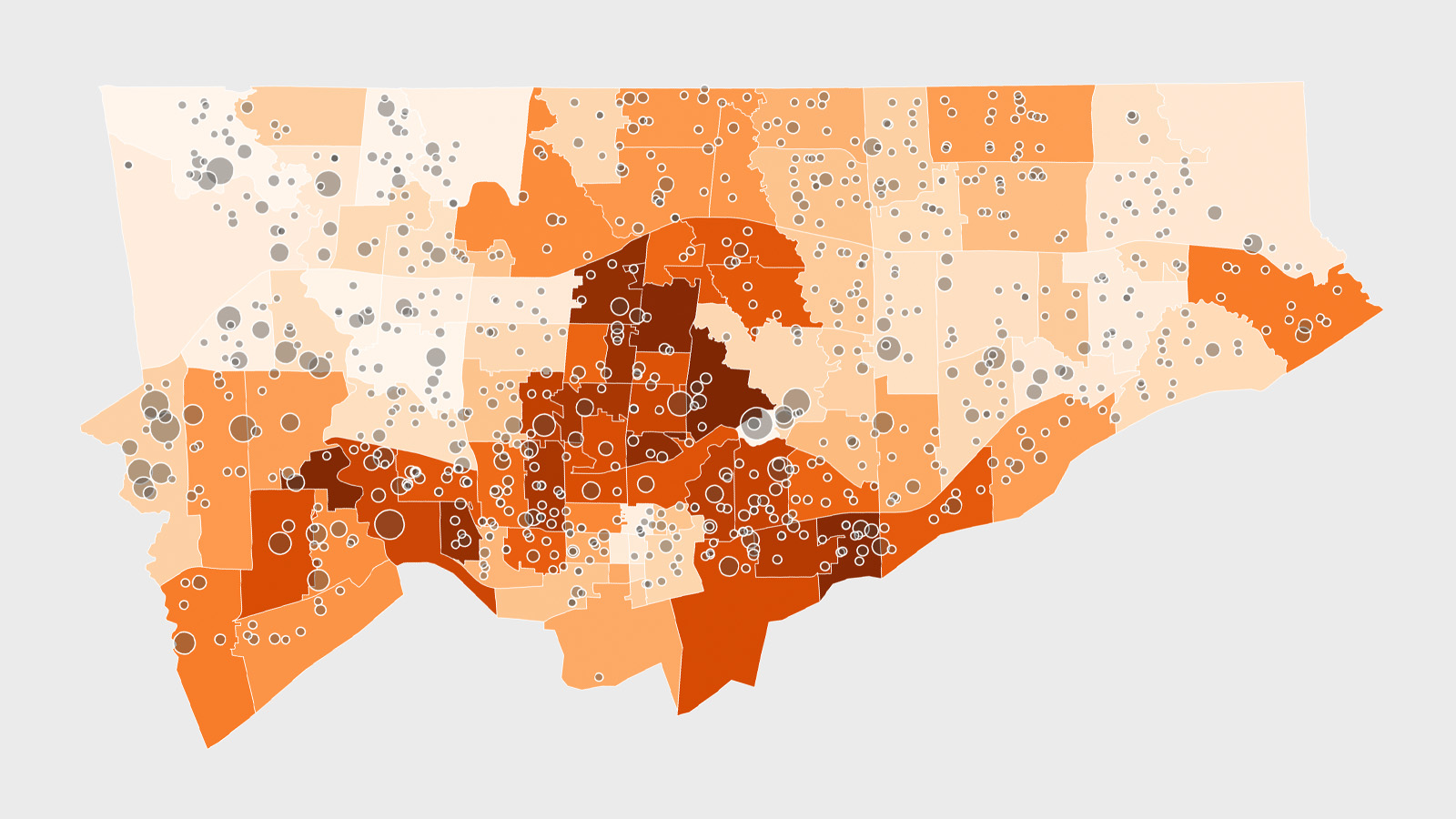

In fact, entire swaths of Scarborough and Toronto’s northwest have vaccination rates that are less than half of the city’s overall rate. Importantly, neighbourhoods that are home to schools with the largest COVID outbreaks and most numerous infections so far this academic year are among the least vaccinated.

These early results from Toronto’s junior vaccine campaign come at a critical juncture in the pandemic, with rising cases, larger and more frequent school outbreaks, and the emergence of Omicron. The slow uptake in the parts of the city that need them the most is concerning and means that the pattern of infections and school disruptions experienced recently could persist well into the winter months, if no other public health measures are taken.

The latest projections from the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table (which did not account for the more transmissible Omicron) show that, with the current suite of public health measures and assuming 50 percent of kids aged five to 11 are vaccinated by the end of December, daily cases in the province would rise above 1,700 by January, once again straining ICUs. Crank up the percentage of kids vaccinated and the curves flatten; decrease it and the curves shoot up.

Given the pivotal role of vaccinating kids to the overall trajectory of the pandemic, the pace of vaccine uptake among children in Toronto is promising in some ways, but deeply concerning in others. “The fact that, in general, the rates are high is encouraging,” said Ashleigh Tuite, an epidemiologist and mathematical modeller at the University of Toronto. “The thing that is a little bit surprising about that map is that Toronto, before they even rolled out the kids vaccination campaign, was really talking about equity and figuring out how to get vaccines to people who need them.”

Tuite is referring to the city’s strategy to stave off the kind of disparities seen in the early days of the adult vaccine rollout—disparities which are now being repeated, despite on-the-ground efforts to reach those in high-needs neighbourhoods.

Phil Anthony manages Michael Garron Hospital’s school-based clinics and co-leads Toronto’s pediatric vaccine planning table. For him, the low uptake in the priority neighbourhoods is deflating. “It hurts,” he admitted. “There was a lot of effort put into that.”

Anthony’s team has partnered with local schools and community agencies to bring Pfizer doses to students in those targeted communities. In his east-Toronto catchment area alone, Anthony indicated that close to 70 school-based clinics have been held since November 25. They include clinics in places like Thorncliffe Park and Flemingdon Park, where there have been large school outbreaks. So far, those efforts have resulted in just 16 percent and 18 percent of children in Thorncliffe Park and Flemingdon Park with first doses, respectively.

Halfway across the city, Sudha Kutty’s team has been equally active with bringing vaccines into schools in Toronto’s northwest. Kutty is vice president at Humber River Hospital, responsible for their vaccine efforts. “I’m not entirely surprised,” Kutty said, in response to the low vaccination numbers in that area of the city. “As we’ve been doing the school-based clinics, we’re getting reasonable uptake, but definitely not large numbers. I think we’re typically doing in the range of 50 [a day] at a clinic.”

In the Jane and Finch area where Kutty’s team has organized several school clinics, vaccination rates were between 13 to 18 percent as of December 5. For Kutty, the early results serve as a reality check and a reminder that for many areas of Toronto, vaccination is a marathon, rather than a sprint. “It’s just gonna be a bit of slow going and, you know, constant communication, town halls, everything we did the first time around,” she said, referring to the strategies used for the adult vaccine. “I’m not quite sure why we expected it would be different.”

Like the adult vaccine, Kutty thinks that many have adopted a wait-and-see attitude towards the pediatric version. “My gut tells me that the people who waited until the summer to get their first dose are likely gonna wait until February or March to get their kids vaccinated.”

The city’s vaccination rate for kids has risen sharply since the rollout began, driven largely by the rapid uptake in affluent areas. But soon, as we’ve seen with the adult vaccine, those numbers will plateau and, from there, can rise only as fast as the uptake in places like Rexdale, Thorncliffe Park or Malvern. And if Kutty is right, that it’s going to be a marathon, it means that other public health measures—from better deployment of rapid testing, to ensuring in-class HEPA filters are properly used and maintained, to potentially instituting more robust vaccination requirements in certain settings—will be needed in order to buy time for vaccines to gain a foothold in these communities.

For Phil Anthony, the disappointment is deep, you can hear it in his voice. After all, he helped organize some of the most successful vaccine clinics in the world, including the one at Scotiabank Arena that delivered 26,771 doses on a single day in June. Despite the slow start, Anthony takes comfort in the fact that things could have been worse. “I know how much effort has gone into the equity strategy, and I just wonder where things would be without it.” For him, the results reinforce the need to go even harder. “I just think we need to double down on the mobile strategy and the outreach,” he said. “It’s got to be ‘no stone unturned,’ you know what I mean? We’ll get back at it. We just have to.”